Ideas for Writing: Where Do They Come From, and Where Are They Going? (Blog Swap Topic)

Today’s blog post is part of a Secret Subject Swap hosted by blogger Emily Morgan. This topic was sent to me by Jodi Gibson, who asked me to write about “ideas”. Based on that suggestion, I wrote a brief post about my creative writing ideas: where they come from, when they strike me, etc. Thanks for the topic, Jodi!

Where and when do my ideas strike me?

I can’t really pinpoint one main source for my writing ideas, as they seem to come from anywhere and everywhere. I can, however, list some of my favorites.

Sources of My Best Ideas

- Books

- Video Games

- Nature

- Art

- People

Many of my stories have blossomed from ideas that were taken from various books I’ve read and woven together in my mind. Most of my early writing, however, was based on the video games I played all the time, many of which became source material for fanfiction. Now as a biologist, I get plenty of good ideas from observing nature and the behavior of animals, and I’ve also found great inspiration in works of art like music, paintings and photography. But quite a few of my favorite pieces actually grew from ideas that struck me while observing the people close to me, especially my family.

So when exactly do these ideas come to me? Usually when I least expect them. As you can probably tell by the above list, they tend to strike me pretty much anywhere, at any time. But the best ones come while I’m enjoying the things I love most.

How do I get my ideas?

There’s no special routine I follow to inspire new ideas. In fact, sometimes I find that the harder I try to get a good idea, the less likely it is for one to come to me. So instead, I keep on doing whatever I enjoy, and allow the ideas to flow naturally during my “idle thinking”.

That being said, what seems to work especially well to stimulate new ideas for me is researching subjects I find interesting. For example, one of my ideas for a fantasy novel came to me while looking up mythological creatures, as I’ve always been fascinated by ancient and medieval mythology from around the world. Other ideas for science fiction have sparked from the Zoology and Genetics textbooks I used to study when I was in college working toward a Bachelor’s degree in Biology. Even now, I find myself thinking about fictional stories I could write based on the scientific papers I’m working on for Ecology and Evolutionary Biology journals. In short, I don’t really find ideas; they find me.

What do I do with my ideas after I get them?

This is the really exciting part: finding out where a new idea leads. Whenever I get an interesting idea for a story or poem, I make a note of it somewhere on my computer or in one of my notebooks for future reference. Most of them don’t actually go anywhere at first, but I hold on to them anyway in the hope that they’ll prove useful later on (some of them still haven’t). Others start growing into new pieces right away, and in the case of flash fiction and short poems, they can turn into full pieces almost immediately (e.g. “One Mistake“, which was literally finished less than ten minutes after the idea came to me)!

But some of my favorite and most exciting ideas are the ones I get for novels. These I treat with the utmost care, keeping them safe in the back of my mind (as well as a written note, so they won’t be forgotten) and leaving them free to grow in my imagination while I carry on with the rest of my writing and other activities. These ideas are particularly special because they’re the ones that keep coming back, constantly reminding me that I have greater stories to tell, pushing me to release them from the confines of my mind and nurture them with words so they can someday roam free in the outside world as full-grown stories. It may be years before they actually become novels, but I’m sure that when they finally do, they’ll be the ones that were most worth the wait, having blossomed from the most valuable seeds of my imagination.

This has been a special topic post in Emily Morgan’s Secret Subject Swap. To learn more, just follow the button below to her site, and be sure to check out the other blogs participating in the event. Thanks for reading!

Other bloggers in the Secret Subject Swap

Melissa Khalinsky: Melissa Writes

Jodi Gibson: JFGibson

Becky Fyfe: Imagine! Create! Write!

Josefa: Always Josefa

Rhianna: A Parenting Life

Ashley Howland: Ghostnapped

Zanni: My Little Sunshine House

Off The Bookshelf: The Harry Potter Series

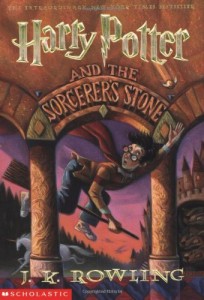

OK, it’s time to share another inspiring selection from my bookshelf. Because last week’s Notable Authors post was dedicated to J.K. Rowling, today’s Off The Bookshelf topic is a complementary review of her most famous works. Since I couldn’t say that only one of these books has inspired me, instead I’d like to briefly cover some general points of all seven of the author’s world-famous fantasy novels: the Harry Potter series.

Summary

First published in the United Kingdom by Bloomsbury (June 1997) and in the United States by Scholastic (September 1998), the Harry Potter series consists of seven novels primarily in the fantasy genre, written for a target audience of young readers from children to young adults. The books tell the coming-of-age story of Harry Potter, a wizard boy who gained fame in the underground wizarding world as a baby after mysteriously surviving an encounter with the Dark sorcerer who terrorized the magical community and killed his parents. The series focuses mainly on Harry’s adventures with his friends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry between the ages of 11 and 17, with each book taking place over one year of the characters’ lives, all strung together through a story arc about the young protagonist’s quest to unravel the mysteries of his life and ultimately destroy the power-hungry Lord Voldemort to save the magical and nonmagical worlds from his evil reign once and for all.

Review

The Harry Potter books have gained incredible success since the first publication of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (if you’ll forgive my use of the American title, since it’s the one with which I’m most familiar), and with such high popularity and critical acclaim, it’s easy to see why. Rowling’s intricate world, compelling characters and engaging storyline quickly drew in millions of readers worldwide, and boosted the novels to become the best-selling book series in history by mid-2011.

Complete Harry Potter Collection – Scholastic hardcover

(CC Image by Stephan Starnes via Flickr)

Although it’s mostly considered fantasy for its predominant theme of magic, Harry Potter also falls under such genres as mystery, thriller and coming of age. This makes it a very versatile and unique read, which may partly explain its enormous success. Despite appearing as a children’s story about wizards on the surface, the series has many levels to it that make it appealing to a broader range of readers. For instance, those who don’t care so much for fantasy might still enjoy Harry Potter as an adventure story at its core, or for its mystery elements, or even as a tale about a young boy trying to find out who he really is. Aside from its overlapping genres, the author also made a point of allowing various themes to blossom throughout her work, including the trials of adolescence, political subtexts, and especially death.

One of the most notable achievements of this series was the fact that it encouraged so many children to read. Yet there was more to it than just getting kids to pick up books they would normally consider above their reading level. As one of the children of the Potter generation, I can attest to the special experience of growing up with the main characters. I read the first book when I was very close to 11 years old and finished the last one not long after turning 17, and because of the way the series gradually progressed into darker themes with each new book, Harry Potter was the key work of literature in my transition from lighter children’s stories to more mature fiction, helping me to develop both as a reader and as a writer.

There’s no question that these books will forever be revered throughout the history of literature, not only for their record-breaking commercial success, but for their tremendous cultural impact. The series has inspired an entire generation of young readers, and it will always hold a special place in the hearts of the millions who have been touched by the magic of Harry Potter.

Inspiration

If Roald Dahl first hooked me on fantasy stories with Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, J.K. Rowling kept me forever loyal to the genre with Harry Potter. As I like to put it, “I came for the chocolate factory, and stayed for the wizarding school.”

Harry Potter has been a huge inspiration to me since my childhood, as much in fantasy specifically as in the rest of my writing in general. The books have opened my eyes to a wonderful world of fiction, and they’ve taught me a great deal about the techniques and passion it takes to create a magical universe. I’ve been an aspiring fantasy author since I fell in love with creative writing as a child, and I can honestly say that this series has played a major part in keeping my dream alive for so many years. No matter how many other novels I go on to read and even write throughout my life, the Harry Potter books are and always will be among my absolute favorites.

Notable Authors: J.K. Rowling

Last month, I started a topic on my blog about sources of inspiration for my writing, which I opened with a couple of posts about Roald Dahl and one of his wonderful novels. Now I’d like to continue on the topic by passing the spotlight onto another author who has greatly inspired me in my writing, and since today is her birthday, I decided this would be the best time to include her in the segment. Featured today among my blog’s Notable Authors is world-famous fantasy author: J.K. Rowling.

Bio

Name: Joanne Rowling

Pen Name: J.K. Rowling

Life: Jul. 31, 1965 – present

Gender: female

Nationality: British

Occupation: novelist

Genres: fantasy, tragicomedy, crime fiction

Notable Works: Harry Potter series, The Casual Vacancy, The Cuckoo’s Calling (under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith)

My Favorite Works: All the Harry Potter books, but especially Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (Book 7)

Inspiration

J.K. Rowling is a world-renowned British novelist, best known for her highly acclaimed Harry Potter series. I was first introduced to her work in my childhood, when my best friend at the time gave me the first two books in the series as a birthday present, and it took me less than a chapter to be hooked for life. The author created such a vivid and imaginative world in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (or Philosopher’s Stone in its original UK title) that I remained loyal to the series for the rest of my childhood and my entire adolescence, reading every new book as it came out until finally closing the back cover on the epilogue. Like so many young readers of my generation, I had been captivated by the magic of Rowling’s imagination.

Harry Potter, Books 1-7

Though she’s established herself as a versatile writer, it’s likely Ms. Rowling will always be known first and foremost as a fantasy author, and it’s as such that she’s inspired me in my own writing. The Harry Potter books not only brought me countless hours of entertainment growing up, but they also taught me a lot about the incredible amount of detail that goes into constructing a fantasy world, something I hope to be able to accomplish myself someday. But it wasn’t just her settings that fascinated me; the author also had a gift for constructing characters that I found engaging and relatable. It was interesting that she seemed to know exactly how to write a coming-of-age story for a male protagonist and make his character believable from the innocent age of 11 to the maturity of age 17 and beyond. On top of that, her attention to detail didn’t stop at Harry, for the rest of her characters were just as well-developed, especially the major ones present throughout all or most of the series. With so much work and care put into creating the world of Harry Potter, it’s really no mystery why I was only one among millions of readers worldwide who were touched by Rowling’s amazing stories.

Now I know that this famous children’s series and its supplements aren’t her only works, but because these are the only books of Ms. Rowling’s that I’ve read (so far), I can’t give a subjective review of The Casual Vacancy or The Cuckoo’s Calling yet. However, I can express my admiration for the author’s ability to step outside the fantasy “brand” she established for herself and still manage to create stories that are generally well-received by her audience. What truly amazed me was hearing the recent news about the latter novel, which she secretly published under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith in an attempt to evade the pressure that comes with being one of the most famous writers in the world. Sure, it didn’t become a bestseller until after its author’s true identity was revealed, but early reviews were still mostly favorable considering it was believed to have been written by a debut writer. If nothing else, it’s inspiring to see how Rowling continues to pursue writing in the face of all the hype around her and keep on creating the stories she wants to tell the world.

J.K. Rowling has been an inspiration to me for her wonderful fantasy writing and the joy her novels have brought me for most of my life. Being an aspiring fantasy author myself, her stories have served as great motivation for me to create my own magical worlds with the same level of care and detail that she put into Harry Potter. While I admire Roald Dahl as the author who first inspired me to become a writer, I will always revere J.K. Rowling as the gifted storyteller who kept me on that path for life.

Happy Birthday, Ms. Rowling! And congratulations on all your amazing achievements! From the bottom of this young dreamer’s heart, thank you.

Composition of the Amethystine Variety and Why One Must Abstain From Its Application (or “Purple Prose and Why You Should Avoid It”)

I’m polymerized tree sap and you’re an inorganic adhesive, so whatever verbal projectile you launch in my direction is reflected off of me, returns on its original trajectory, and adheres to you.

– Dr. Sheldon Cooper, The Big Bang Theory (Season 1, Episode 13 – The Bat Jar Conjecture)

Fans of the comedy TV series The Big Bang Theory likely remember this quote from the Physics Bowl episode, when Sheldon reacts to an insult from fellow physicist Leslie Winkle by saying as condescendingly as possible that “he is rubber and she is glue”. However, the fact that he seems to go out of his way to use the most advanced vocabulary possible in his retort only adds to the hilarious running gag of Leslie always managing to beat her rival at a game of wits.

So what lesson should novice writers be learning from Sheldon’s backfired comment? That trying too hard to sound smart often has the opposite effect than what you might expect, that is, it hurts more than it helps.

What is this amethystine composition of which you speak?

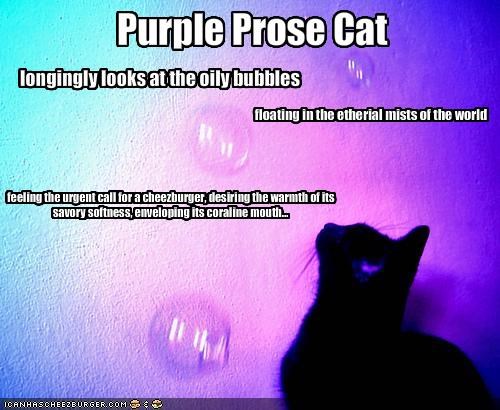

Writing that is overly decorated with fancy words and elaborate details is known as “purple prose”. It’s an especially common practice among inexperienced writers, who often believe that to write a really good story (or improve upon an existing dull one), one needs to dress up the prose with as many big words as possible to make their work look sophisticated. Basically, beginners seem to have this grand illusion that great literature is that which stands above the level of everyday speech.

Purple prose: Contemplate this exquisite aubergine blossom of the Rosaceae family

Everyday speech: Look at this beautiful purple rose

But here’s the problem with that logic: everyday speech is the level where most readers are, and more importantly, where they want to stay. Readers today don’t want to bore their way through long descriptions or have to pause at every other page to look up half the words they just read in the dictionary. They want writing that’s simple, that they can understand and find relatable, similar to the language they use themselves in the real world.

So I’ve been writing erroneously… I mean, wrong all this time?

Calm down, and take a second to note that I said “similar to”, not “the same as”. It’s OK to use some higher-level vocabulary and detailed narration in your stories, for when done in moderation and in tone with the style of the work, these can actually add to the quality of your writing. The danger is using these tools in excess, because after you’ve passed a certain point in flowering up your prose, these details will begin to draw attention to themselves and away from the flow of your story. To sum up, a little is fine, but too much is bad. Write with caution.

Now before anyone accuses me of hypocrisy, allow me the chance to admit to this embarrassing fact: I am guilty of writing purple prose. Even if I don’t always choose the fanciest synonyms I can find to replace everyday words, I love decorating my writing with adjectives and adverbs, and I tend to use intermediate-level words where common ones would work just fine. That being said, I used to be much worse. When I first started writing, I had this idea that nobody would want to read stories written in the plain language of a ten-year-old, so even though I was already well-read for my age, I went out of my way to find “bigger and better” words for my fiction. It wasn’t until I started learning about common writing mistakes as a young adult that I realized how flowery my early writing was, and I’ve since been gradually cutting the bad habits of my childhood. So take it from a writer who’s still breaking out of the novice phase: tone down the purple and focus on writing simple prose. Your readers will appreciate it.

It’s worth noting at this point that as strongly as most experienced writers will argue against this practice, prose style is and always will be subjective. It’s entirely possible for a writer to not only be aware they write such elaborate prose, but actually do it on purpose. So if you’re a beginning writer guilty of this trope, don’t feel bad right off the bat. Maybe your goal is to imitate the exact styles of writers like William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens and Jane Austen, and that’s fine. Just know that unless you’re going for satire, most of the audience who would take your work seriously has probably been dead for a few hundred years.

It’s worth noting at this point that as strongly as most experienced writers will argue against this practice, prose style is and always will be subjective. It’s entirely possible for a writer to not only be aware they write such elaborate prose, but actually do it on purpose. So if you’re a beginning writer guilty of this trope, don’t feel bad right off the bat. Maybe your goal is to imitate the exact styles of writers like William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens and Jane Austen, and that’s fine. Just know that unless you’re going for satire, most of the audience who would take your work seriously has probably been dead for a few hundred years.

But I want to be taken seriously today! What should I do?

Don’t worry, the “purple prose bug” is treatable! For those of you aspiring writers who wish to establish yourselves before you try to follow the great authors who bend the rules, here’s a quick list of common purple prose mistakes and how you can avoid them:

1) Excessive detail. Yes, describing the setting of a scene before the action starts is often essential to telling a good story, but please don’t go on for a dozen pages about the hundred different colors in the sky or the history hidden in every brick of every building. Just because authors like J.R.R. Tolkien and Victor Hugo could get away with it doesn’t mean you can. One paragraph should be enough to set your scene, but no more than two.

2) Overly decorated nouns and verbs. If you’re one of the millions of readers who have read all of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books, you may have learned that nouns and verbs should almost always include a “modifying friend”. But Rowling is an exception, a world-famous author of one of the best-selling book series in history, which you are (probably) not. That means she can do whatever she wants with her writing, whereas you should practice creating basic prose before you work too hard to copy her style. Try not to use too many adjectives and adverbs in your writing. Though this may seem counterintuitive, many famous writers would agree that less is more. If you don’t believe so, read a story by Ernest Hemingway or Mark Twain, and you’ll see how writing can be great without the need for too many “attachments”. To quote Twain, “When you catch an adjective, kill it.”

3) Said bookisms. This is one of the most common mistakes made by beginning writers: the constant use of alternative verbs for the word “said”. There’s a general belief that when it comes to writing dialogue, “said” is too plain and overused, so writers should go out of their way to replace it with words like “asked”, “muttered”, “hissed”, etc. As a teenager, I used a lot of these in my writing; I wouldn’t be surprised if I read back a dialogue-heavy scene from one of my old stories and found at least three pages between consecutive uses of “said”. But even famous authors seem to be guilty of this sometimes (I’m given to understand there’s an entire blog devoted to poking fun at the purpleness of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series), so don’t feel too bad if you find your own writing full of these bookisms. The important thing is that you know you should fix them. Dialogue should convey tone by itself, no extra tags required.

4) Too much “fancy vocabulary”. Continuing from the example of “said”, some writers tend to try and find as many advanced-sounding synonyms as possible to substitute the common words in their stories. While this may be fine once in a while, you shouldn’t run to the thesaurus for every other word you want to write. Otherwise, you’ll end up sending your readers to the dictionary just as frequently. It’s great to learn new words, but think about it for a second: the more time you put into driving your audience to read another book, the less time they’ll spend reading yours. Try to stick to vocabulary that your readers will understand, and if you must throw in a higher-level word now and then, at least have the courtesy to make its definition clear in context.

5) Exaggerated sentiment. There isn’t a lot I can say here except that this is pretty much a writer’s attempt to manipulate the reader into reacting a certain way to their writing. Going back to the first item on the list, if you throw too much rhetorical writing into your stories, it comes across as you trying too hard to evoke specific emotions from your readers, which more often than not will have the opposite effect. Trust your audience to understand what you’re trying to tell them. If you write it plainly enough, they will feel it.

Purple prose is a dangerous habit of many writers, and while it may be OK for some, most should make a point of avoiding or overcoming it, no matter how difficult this seems. If nothing else, choosing to create simple and clean prose is a sign of respect to your work and your readers, so take care with your style of writing. I’m certainly still trying.

So what are your experiences with purple prose? Have you read stories that you found too flowery for your taste? Were you (or are you) ever guilty of making these mistakes yourself?

The Power of an Introverted Writer

I love TED Talks. From science to politics to social topics, they’re always inspiring to watch, and they’ve opened my eyes to quite a few fascinating perspectives in a wide array of global issues. But one Talk that really – if you’ll pardon the pun – spoke to me as a creative and soft-spoken individual was author Susan Cain‘s take on the power of introverts.

This video was shared with me some time ago by my best friend, a young man just as introverted as I am who found this Talk very inspiring for people like us (and those who wish to understand us). Instead of running through the entire 19-minute transcript, I thought it more convenient to embed the video here for others to watch themselves. Enjoy!

(Note: in case it doesn’t load properly on the page you’re reading, you can watch the Talk on its original TED page here, where you can also find a full transcript).

[ted id=1377]

Since there isn’t much I can add that Mrs. Cain hasn’t already covered perfectly well, I just want to give a brief review of how I can personally relate to her Talk and the ways I consider her case valid to my experience in creative writing.

Avid reader

I too spent much of my childhood reading books. Although most of my reading time was in the privacy of my own bedroom, I did make a habit of carrying books in my backpack to enjoy at school. Whenever I felt exhausted by the energy of my surrounding classmates (which was quite often), I would find a quiet corner and retreat into the world of my books to recharge. Maybe it seemed like an overly reclusive practice, but in a way, my books were like a lifesaver that helped me through my grade-school years.

Introversion vs. Shyness

I’m glad Mrs. Cain brought up this distinction, as it’s important to know there’s a difference. A great example of this is my dad: he’s one of the most social and friendly people I know, but when it comes to work, he much prefers handling tasks on his own. My dad is what some might consider an unusual type of individual: an outgoing introvert.

Having noted this, I’d like to point out that I’m both introverted and shy. The main difference is that my shyness is a trait that I’d like to be able to overcome, at least to the point where it no longer holds me back from doing most of the things I’d like to try in my life; whereas my introversion is a characteristic that I will always be proud to consider an important part of my personality. In other words, I’m not always happy about being shy, but I am always happy about being introverted.

In the classroom

At the risk of sounding boastful, I was an excellent student growing up. I’m talking straight-A, perfect-record, all-my-teachers-loved-me excellent. And I honestly believe that my introverted personality played a major role in my academic achievements. That’s not to say that extroverted students were beneath my level; my best friend in middle school was an extrovert, and she was in the gifted program with me. My low-key approach to my studies just worked best for me because the time I used to work on my own allowed me to think much more clearly.

However, I do remember some classes I took in elementary and middle school where the desks were arranged in the pods described in the above video, so I’d have to be facing at least three other students and often work with them in group assignments. I understood the point of this arrangement, but to be frank, I much preferred the rows.

Solitude = creativity

I agree with the speaker’s argument that we shouldn’t stop collaborating altogether, nor should we stop valuing the great qualities that extroverts bring to the table, but we should at least have a decent balance between teamwork and solitude, since the latter is often important for creativity to blossom. I’ve always found that my best ideas come to me whenever I’m alone with my thoughts, especially when I have plenty of time to daydream (one of my favorite pastimes). But I know that writing isn’t a completely solitary profession, which brings me to my final point…

The budding writer

I love creative writing for the freedom I feel it gives me. I’m in total control of my ideas, my characters, my settings and plots. But there’s only so much enjoyment I can get out of writing on my own, because after I finish shaping my ideas into my stories, I can’t wait to share them with the rest of the world, and that requires stepping out of my introverted shell.

I know that after I finish my novels, I’m going to have to put them out there somehow, helping to promote them and get them to the readers that I want to inspire. And I think I’m OK with that. As long as I still get to be my introverted self (and be appreciated for it), I’m OK with having to face the extroverted lifestyle once in a while for the sake of that all-important balance for which Susan Cain so strongly advocates. Looking up to the countless introverts who have graced the world with their amazing qualities, I hope to have equal courage to – as she so wonderfully puts it – speak softly.

What about you? Are you an introvert or an extrovert (or an ambivert)? How well can you relate to Susan Cain’s Talk? Do any of these notes apply to you?

Writer’s Toolkit: Journal

I realize I haven’t written a Writer’s Toolkit piece since my review of What If? Writing Exercises for Fiction Writers. For my second post in this topic, instead of a specific book, I’ve decided to write a brief review of the importance of a more general tool that every serious writer should have at their disposal: a personal journal.

Writer’s Journal

I’m sure we all remember the innocent grade school days when the most trustworthy friend we had was that little book sitting in our bedroom, whose sole purpose was to guard our deepest thoughts and feelings. Many of us at one time or another have owned a notebook of some sort that we kept as a diary or journal (I myself kept quite a few during my childhood and adolescence). It was our outlet for the private ideas we couldn’t share with anyone else, an emotional release that left us with the satisfaction of knowing our secrets were still safe from the rest of the world. But for the budding writers among the countless young people pouring their hearts out in secret, that book was so much more. While all the other children and teenagers would keep their journals and diaries as a vent, we writers would keep them as a net to catch the little seeds dispersed throughout our lives that could eventually grow into our stories.

A journal is an important tool for any writer mostly because it serves as a log of the potential story ideas that might otherwise elude us. To give a personal example, during my college years, I kept a journal in my backpack in which I would write the thoughts and emotions I experienced while at my university. The book was a record of my college life, and several of its entries – about which I might otherwise have forgotten – later became inspiration for my fiction writing. Without that journal, I likely would have missed a lot of opportunities to find relatable traits for my characters or interesting scenarios for stories.

But my journals have helped me in an even greater capacity. Writing down my thoughts and being able to read them back objectively has allowed me to gain a better understanding of how I tend to see the world around me, and consequently, learn how I can best channel my ideas into my writing. On top of that, while my fiction pieces are for showcasing my refined writer’s voice, my private journals are for unleashing the raw voice fresh out of my mind that has yet to be shaped into the stories I want to tell. As I’ve come to realize, even creative writing comes with basic rules when intended for other readers, but when writing just for yourself, there are absolutely no limitations except you.

Summary

Advantages of Keeping a Journal

- Intellectual and emotional release

- Keep a record of possible ideas for future stories

- Objectively observe and understand the voice(s) in your head

- Unleash your raw creativity without inhibitions

Based on my experience (as well as similar accounts from other more established writers, including authors to be mentioned in future Writer’s Toolkit posts), I highly recommend keeping a personal journal as a good exercise for any writer. Sure, many of us probably don’t have the time to fill half a dozen journal pages (or even one) every day, especially in these modern times of ultra-busy lives filled with a hundred daily tasks that leave us exhausted by the time we get a chance to crawl into bed. Still, it’s good practice to set aside at least a few minutes every day to jot down some key observations of recent events, no matter how simple. Remember, even if your thoughts don’t seem particularly interesting at the time of writing, you never know if they could prove useful in the future!

Thanks for reading! Now, if you haven’t already done so, go and start your journal! Happy writing!

An Attempt at a Clever Title: The Topic of the Blog Post

Confused about the title? Or maybe you’re confused about my asking if you’re confused about the title? Or maybe you’re confused about my asking if you’re confused about my asking if you’re confused about the title? Or maybe you’ve had enough if this nonsense and just want me to get to the point?

This week’s creative writing topic is an interesting trope of which I’ve become rather fond over the course of my own writing: a technique known as “lampshade hanging“, or simply “lampshading”. It’s an idea I first learned about when reading TV Tropes, and because of the way I often see it being employed in humorous writing, it’s quickly becoming one of my favorite devices in fiction. But you probably don’t care yet what I think about it; you’re just waiting for me to explain what it is so you can decide whether you’d like it too. Unless you went ahead and skipped to the next paragraph before reading this one and already realize how I’ve been incorporating the trope into this blog post. Am I right?

This is not the lamp you’re looking for…

OK, no more stalling. Lampshade hanging is a trick employed by writers to address any noticeable implausibility or obvious trope usage in a plot by drawing attention to it… and then moving on. But wait, why would you want to point out your story’s flaws in the first place? Counter-intuitive as it may seem, this exercise does have a few advantages:

- It proves you aren’t trying to get away with a questionable plot development by showing your audience that you’re also aware of the absurdity;

- It establishes a sense of realism in your story by demonstrating that your characters are just as skeptical about the implausibilities in the plot as the real-life people following it; and

- It’s a way to beat critics to the punch of deprecating you for the “mistakes” you already know are in your story.

Need an example? Here’s a rather brilliant one from my favorite moment in the 2000 Disney film An Extremely Goofy Movie, when Bobby Zimmeruski randomly realizes something strange about the world around him…

You know you’ve always wondered the same thing…

The best part? This question is almost immediately dismissed and never comes up again for the rest of the movie!

It should be noted that whenever a writer “hangs a lampshade” on a particularly glaring plot hole, it could be taken as a hint from their subconscious about the true extent of an unforgivable absurdity in an otherwise serious work. Of course, the technique can also be observed in use to the extreme in stories that are intended to be especially humorous and even self-aware, which (when done well) can be very entertaining (like in this product placement clip from the comedy TV series 30 Rock, which brilliantly demonstrates Tina Fey’s mastery of humor tropes). Mostly, though, it works just fine when used in moderation, kind of like a brief comic relief to complement the action in the rest of the story.

Bonus note: aside from “lampshades”, the practice is also known as hanging a “red flag”, “lantern”, or “clock”. The trope is referred to as “lampshade hanging” in my blog because it’s the most common term used on the TV Tropes website, which in turn attributes the phrase to Mutant Enemy.

While I don’t hang lampshades often in my fictional works, I do enjoy throwing them into my blog posts now and then, which I tend to use for humorous purposes as a personal reminder not to take myself or my writing too seriously (a flaw of which I’m painfully guilty, possibly evidenced by the fact that I don’t like to end phrases with prepositions). Hopefully my readers find them entertaining, or at the very least, tolerable. I do enjoy practicing lampshade hanging, and if you like to keep an element of comedy in your own writing, you might like to take it up too!

Now if you’ll excuse me, I must go do extensive research for the next blog topic on which my novice writer’s knowledge is still relatively limited. Thanks for reading!

Three Random Grammar Peeves That Are Socially Acceptable

I don’t usually like to get picky about grammar, save for when I’m editing my own writing (or teasing my closest friends). Every now and then, however, I catch a few minor “mistakes” in the writing and speech of others that jump out at me. I use quotation marks because they aren’t necessarily wrong; I just tend to find them a bit odd, and occasionally a little annoying. Maybe there are others who would agree, and maybe sometimes it’s just me being my regular nerdy self.

I don’t usually like to get picky about grammar, save for when I’m editing my own writing (or teasing my closest friends). Every now and then, however, I catch a few minor “mistakes” in the writing and speech of others that jump out at me. I use quotation marks because they aren’t necessarily wrong; I just tend to find them a bit odd, and occasionally a little annoying. Maybe there are others who would agree, and maybe sometimes it’s just me being my regular nerdy self.

Just for fun, today’s topic brings you three random “pet peeves” of mine that are widely accepted as understandable language. You can decide for yourself where you stand on these…

1) When “could” really means “couldn’t”

I admit that it bothers me a little to see people using the phrase “I could care less” when they clearly mean to say “I couldn’t care less”. The logic behind the phrasing is simple: if you “couldn’t care less”, you’ve reached the limit of how little you can care about something, whereas if you “could care less”, there’s still a little part of you that does care and has yet to be eliminated.

I’ve heard a couple of theories as to how the “could” variation emerged in colloquial speech. One states that it was originally meant to be used in a sarcastic manner and not taken literally. Another explanation, according to American linguist Atcheson L. Hench, is that slurred speech has garbled the “couldn’t” of the correct phrase into the “could” that most people hear (American Speech, 159; 1973).

Which explanation is the truth? I have no idea. All I know is that I always use the original phrasing in my own speech, and if anyone doesn’t believe me when I say it’s the “correct” form, I couldn’t care less.

2) The American pronunciation of “niche”

I’ve lost count of all the playful arguments I’ve had with my best friend over this word. Our debates usually play out the same: I tell him the correct pronunciation is “neesh”; he answers back that people say “nitch”. I explain that the word comes from French, so its original pronunciation should be maintained; he argues that we’re American and we should adapt to the way most Americans speak. I ask him if by that logic, we should also start saying “ba-LET” and “gor-MET”; he claims that’s not the same thing because everyone says “ba-LAY” and “gor-MAY” without a problem. Then we toss the word “niche” back and forth, each of us insisting that our pronunciation is correct, until we both get tired and agree to disagree before changing the subject. After the entire discussion is over, we’re still friends.

Albeit friends who each still think they’re right. (Neesh.)

3) The alternative spelling of “doughnut”

To be fair, this one is more of a personal preference than an actual pet peeve. I understand that both “doughnut” and “donut” are equally acceptable spellings; I just prefer the former because it seems to me – for lack of a better description – “more correct”. It is the original spelling, after all; the invention of doughnuts can be traced back as far as the 19th century, but the earliest known printed use of the word “donut” is only from 1900 (Peck’s Bad Boy and His Pa by George W. Peck). Not to mention, “doughnut” also feels more complete: just by looking at the word, you can already tell what the main ingredient is…

Still, both spellings are equally pervasive in American English, though “doughnut” seems to be the more common form outside of the United States. Oxford Dictionaries list “donut” as the alternative spelling of “doughnut”, making the longer word the traditional option for more formal writing, yet the shortened form is popular for references like company names (e.g. Dunkin’ Donuts). Even my best friend (yes, the same young man who advocates so strongly for “nitch”) insists that “donut” is the best spelling because it’s modern, and thus more appealing to the readers of today. As he says whenever I insist that “doughnut” is the better choice, “Take it up with The Donut Man!”

These are just a few random examples of minor deviations from my grammatical standards. Like I said, they aren’t really wrong; it’s all a matter of preference. And call me a geek if you like, but I simply chose the alternatives that I deemed grammatically correct.

So what about you? Can you relate to any of the examples listed above? Do you have pet peeves of your own that don’t really detract from communication more than they just annoy you?

Looking in the Literary Mirror: Seeing Yourself in Your Characters

Once upon a time, there was a beautiful princess who lived in a dark castle guarded by a fire-breathing dragon, always dreaming of the day a young man would come and rescue her from the evil sorcerer who had kidnapped her and trapped her there. One day, a brave knight stormed the castle on his trusty steed, slew the dragon and killed the sorcerer. He rescued the princess from her lonely tower and took her back home to her kingdom. The king and queen were so grateful to the knight that they offered him their daughter’s hand in marriage, to which he and the princess gladly agreed. The knight and the princess were married, and they lived happily ever after. The End.

This is a classic fairy tale formula: villain has damsel, hero goes after damsel, hero defeats villain, hero and damsel fall in love and live happily ever after. The exact course of events may vary from story to story, but the basic idea is usually the same. Also universal in romantic fairy tales, if you’ll notice, are the character archetypes present in the plot. So pervasive are they in fiction that we’ve been trained from childhood to recognize them on sight: the handsome prince or the knight in shining armor; the beautiful princess or the young lady in need of rescue; the evil villain who stands in the way of true love, etc. And while these characters clearly serve their purpose when it comes to telling a well-rounded story, we as writers must ask ourselves why they don’t (or at least shouldn’t) appeal to us as satisfactory vehicles for the tales we wish to tell.

The main problem with the fairy tale characters is that they’re “plug-in” types. They’re like mass-produced instant ramen noodles: conveniently cheap and easy to prepare, but not exactly a healthy choice. When basic character profiles are used excessively over the years, they inevitably become clichéd and uninteresting. And intelligent readers don’t want clichéd and uninteresting; they want to see through the action on the pages to glimpse another level of the characters. They want depth.

The main problem with the fairy tale characters is that they’re “plug-in” types. They’re like mass-produced instant ramen noodles: conveniently cheap and easy to prepare, but not exactly a healthy choice. When basic character profiles are used excessively over the years, they inevitably become clichéd and uninteresting. And intelligent readers don’t want clichéd and uninteresting; they want to see through the action on the pages to glimpse another level of the characters. They want depth.

As writers, we are obligated to act as intelligent readers of our own works, even super-intelligent. We need to have a complete understanding of our characters that transcends our readers’ perceptions. To achieve this, we have to provide our characters with personal details that make up a life outside of the main action in the story, a life that will save them from being labeled as “ordinary” and keep our readers intrigued. So how exactly do we manage this?

Amelia stared out of the window of her room for what the scratched-up wall behind her claimed was the thirty-second day in a row. Yet again, she found herself longing to visit the rolling hills in the distance. It was so boring in her room: all the walls had already been painted twice in a dozen different colors, and she was out of embroidery supplies for the third time that week. She wanted to go outside, where there was fresh air and animals to chase and adventures to be had every day. She wanted her freedom back.

Good fictional characters are like real people: unique. They have backstory, flaws, fears and dreams. The best ones also have personal goals that often serve the important purpose of driving their stories forward. Can you think of anyone else who might fit that description?

Petrus, the lonely philosopher that she liked to visit on occasion, had foolishly thought it would be a good idea to get a small pet dragon to keep him company in his otherwise abandoned castle at the far edge of the forest. The second Amelia had stepped through the gate, the darn beast had chased her across the courtyard straight into the building, where her friend had told her that until he could find a way to subdue the dragon, she would have to stay inside where it was safe. That was a month ago.

Something I’ve noticed that I tend to do a lot when writing fiction is insert elements of my own personality and ideals into my stories. Although its usually done subconsciously, I feel this has helped me tremendously when trying to create believable characters. It isn’t just me, of course; many of the stories I’ve read seem to reflect characteristics of the writer behind them, as much the favorable as the less-than-flattering. Speaking from my experience, not only is this a practice that’s probably very common among knowledgeable writers, but that should really be encouraged among beginners, especially those who are prone to following the flat “Once upon a time” formula.

Jack couldn’t remember how he had ended up here. One minute, he was standing atop a tree beside a stone wall, trying to figure out where he was after being lost for an hour; the next, he was waking up in the courtyard on the other side of the wall next to an unconscious dragon and a huge broken branch. Before he knew it, an old man in a dark robe and a young girl his own age had run out of the nearby castle and were thanking him for his heroic deed. What heroic deed? Jack insisted he was no hero; he was just a squire who’d gotten lost after being separated from the knight with whom he was traveling to the kingdom. Nonetheless, the philosopher was grateful for this stroke of good luck, and requested that Jack accompany Amelia back home. She knew the way, he assured the boy, and her father was sure to reward him handsomely for his deed. The man was, after all, an advisor to the king himself…

Writing yourself into your stories has a few major advantages:

- It makes it easier to write in a way that readers will find relatable;

- It helps you develop a better familiarity with the characters you’re creating (after all, who knows you better than you, right?); and

- It allows your readers a subtle means of getting to know the writer behind the words.

Alice Through the Looking Glass, by Lewis Carroll

(Image via Scientific American)

The story shared here is just a silly fairy tale twist that I improvised, but which still serves to demonstrate how I tend to base elements of my writing on myself. Amelia’s painted walls and embroideries reflect an artistic side, though the adventurous dreamer in her is also a comment on my idealistic views about women who are independent thinkers. Petrus, being a philosopher, is a type of character who’s expected to be intelligent, but who still isn’t immune to bad decisions brought on by negative emotions like loneliness (why else would anyone get a pet dragon if they had no clue how to handle it?). Even Jack is a quirky character of humble status who would hardly consider himself a hero had he not been in the right place at the right time.

The traits I’ve taken from myself give all these characters a certain depth that separates them from their two-dimensional parallels in the first story and (hopefully) makes the second story a more interesting read. In this way, by writing yourself into your own stories, you can add color to your characters’ profiles and create tales that not only appeal to your intelligent readers, but also give them a chance to catch glimpses of the unique person that is you.

Amelia bid Petrus farewell as he fettered the unconscious dragon, thanking him for taking such good care of her for the past month. She then led the way to the nearby kingdom that was her home, and after reuniting with her worried parents, she introduced Jack as her new friend. The boy was awarded knighthood for taking down a dragon and saving the advisor’s daughter, and he and the girl quickly became best friends. For several years, Jack and Amelia continued to visit Petrus together and pursued many adventures throughout their adolescence, until at last they reached adulthood and realized they had fallen in love. The two friends were eventually married, knowing they’d be very happy together for the rest of their lives. Their greatest adventure had only just begun.

What about you fellow fiction writers? How do you draw inspiration for creating your characters? Do you recognize traces of yourself in any of your stories?

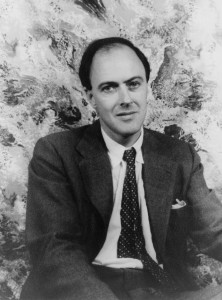

Notable Authors: Roald Dahl

So last week, I talked about a book that I loved as a child: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Continuing on the subject of inspiration, I wanted to create another subtopic focusing on authors whose work has inspired me in my own writing, and it seems only fair to start with the same author of the wonderful book I’ve already reviewed. Kicking off the Notable Authors segment of my blog is storyteller extraordinaire and one of my favorite writers of all time: Roald Dahl.

Bio

Name: Roald Dahl

Pen Name: Roald Dahl

Life: Sept. 13, 1916 – Nov. 23, 1990

Gender: male

Nationality: British (born in Wales), Norwegian descent

Occupation: novelist, short story writer, screenwriter, fighter pilot (WWII)

Genres: children’s literature, fantasy, mystery, nonfiction

Notable Works: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Fantastic Mr. Fox, James and the Giant Peach, Matilda

My Favorite Works: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda, The Umbrella Man and Other Stories

Inspiration

Roald Dahl was my favorite author growing up, and with good reason. Having captivated me at the age of nine with his 1964 novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, he quickly drew me into his fantastic world with more children’s books like Matilda, Fantastic Mr. Fox, The Witches and several others. His unique style of storytelling was very entertaining to read, for he always seemed to know exactly how to paint a mental picture from the perspective of a child, which is much more appealing (and less patronizing) than an adult trying to describe the events of a story in a way that children will understand. Reading each of Mr. Dahl’s novels as a kid, I felt as though I were being told a story by someone who understood exactly how I saw the world, and who knew exactly what I wanted to find in the pages of a book. It may seem odd, but whenever I was reading one of his stories, I didn’t see him as just an author; I saw him almost as a friend.

Matilda and Miss Trunchbull, Matilda

(Illustration by Quentin Blake)

Something I always loved about Dahl’s children’s books was the fact that his heroes were usually children. Charlie Bucket, Matilda Wormwood, the unnamed protagonist of The Witches (named Luke Eveshim in the 1990 film), among others, all live incredible adventures before even having reached adolescence. For the preteen me, it was wonderful to read about heroes who were my age; it made me feel like it could just as easily have been me taking a tour through a magical chocolate factory, or developing telekinetic powers, or executing brilliant plans to defeat witches or cruel headmistresses or nasty adults of any sort. That’s another interesting detail about the author’s stories: just as the heroes are often children, the villains are often adults. And honestly, could anything be more relatable to a young reader?

But Mr. Dahl’s brilliant storytelling skills were not limited to children’s fiction. He wrote a fair amount of excellent short stories for older audiences; one such compilation – The Umbrella Man and Other Stories – contains some of the most delightfully creative short pieces I’ve ever read in a book. His autobiography, Boy: Tales of Childhood, includes hilarious accounts of events that I could hardly believe were true stories (my personal favorite is the Great Mouse Plot of 1924, which romantic comedy fans may remember as the story Meg Ryan reads to the children in the bookstore in the 1998 film You’ve Got Mail), but which certainly explain the colorful stories he would go on to write later in his life. With numerous awards and tremendous merit to his name, it’s clear that Dahl was talented at entertaining readers of all ages alike.

Roald Dahl is one of my heroes. He introduced me to a magical world that I could visit anytime I wanted to escape from reality, and he was the first author ever to inspire me to pursue creative writing. His stories have touched me and will remain forever embedded in my heart, and for that, I will always admire him as one of the greatest storytellers whose work I’ve had the pleasure of reading. Thank you, Mr. Dahl, for your wonderful gift! You will never be forgotten.

Recent Comments