by Naomi L. | February 5, 2014 | Blog, Creative Writing |

Language is a beautiful thing. We use it every day to translate our thoughts and convey our feelings to our fellow human beings, and that has undoubtedly helped us to progress as a species. But the use of language is not without its flaws; words get mixed up and can be misunderstood if people don’t know how to use them properly. So just for fun, here are four words that are commonly misused in speech and/or writing in the English language. Enjoy!

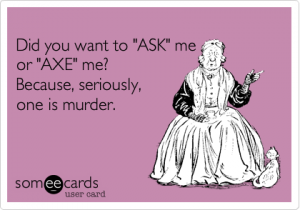

1) If you have a question, please don’t “axe” me…

OK, I know people aren’t really trying to say “axe” in this context, but the common mispronunciation of the word “ask” still bothers me enough to warrant a place on this list. I admit that I cringe a little whenever I hear someone say they want to “aks” a question; every time, the editor in my head screams “Ask! Ask! ASK!” Yes, I understand that people in different regions have different ways of speaking, and old habits are hard to break. But that doesn’t make this mistake OK.

OK, I know people aren’t really trying to say “axe” in this context, but the common mispronunciation of the word “ask” still bothers me enough to warrant a place on this list. I admit that I cringe a little whenever I hear someone say they want to “aks” a question; every time, the editor in my head screams “Ask! Ask! ASK!” Yes, I understand that people in different regions have different ways of speaking, and old habits are hard to break. But that doesn’t make this mistake OK.

So if you have a question, please don’t “axe” me. I don’t want to die.

2) “Defiantly” is not an alternative spelling for “definitely”.

Of all the spelling mistakes I come across regularly, this is one of those that bug me the most. Every time I see it made, a part of me wants to explain to the so-called language offender that “defiantly” and “definitely” are two completely different words that should never be confused. But people probably don’t notice the mistake because the spellings are so similar, or worse, they assume that one word is the same as the other because the error is so common.

Remember: “defiantly” means “showing open resistance”, while “definitely” means “without doubt”. Hopefully you can “definitely” love someone, but you don’t have to love them “defiantly”!

3) “Ironic” doesn’t mean what you probably think.

I’ve noticed that people sometimes like to use the word “ironic” as a synonym for “sarcastic”. But even though these adjectives have similar meanings, they’re not actually interchangeable, at least in a formal sense. Yes, the definition of “sarcasm” is “the use of irony to mock or convey contempt”, but the uses of these words in speech are still distinct. The best known meaning of the word “ironic” is “happening in the opposite way to what is expected”. Thus, irony is often used as a more harmless humor technique compared to sarcasm.

So whenever you describe an event as “ironic”, you may want to consider whether you really mean “sarcastic”, or vice-versa. ‘Cause you know, it’s sooo ironic when human beings make mistakes.

Even Windows has a sense of irony…

4) If you had “literally” died, you wouldn’t be here to tell the story!

Ryan: Did you see that? What just happened? That was literally a train wreck!

Steven: No, Ryan, it was figuratively a train wreck.

– Go On (Season 1, Episode 12 – “Win at All Costas”)

We all probably know someone who tends to overuse the word “literally” when speaking. “It was literally the best pizza in the world!” “It’s literally a million degrees today!” “The interview was literally a train wreck!” Over time, the word has become a common adverb for conveying exaggeration. However, although it’s technically acceptable in an informal way, “literally” shouldn’t really be used for emphasis, as it means “in the exact sense, without metaphor or allegory”.

So no, the wasp was not “literally” the size of a helicopter. No, you did not “literally” jump out of your skin at the sight of it. And no, you did not “literally” die of embarrassment when everyone laughed at you for running away. Otherwise, the military would be after that giant insect, you’d be an undead heap of raw meat and bones, and everyone would be feeling a horrible mix of confusion and guilt for having killed you with laughter!

What are your thoughts on these misused words? Any others you would add to this list?

by Naomi L. | November 6, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing |

All native English speakers are familiar with this problem: words and phrases that appear similar in spelling, pronunciation or meaning, but that actually have distinct definitions. This, of course, can cause some confusion when writing. After all, it’s not always easy keeping track of the right words for the context we want, and even the most proficient writers make mistakes. But nobody’s perfect, right?

To help you avoid some common (and a few uncommon) grammar pitfalls, here are 25 examples of words and phrases you may be getting mixed up in your writing. Almost all of these items were taken from The Hodges Harbrace Handbook, an excellent resource for beginning and advanced writers alike. Be sure to check it out if you can! Write wisely!

To help you avoid some common (and a few uncommon) grammar pitfalls, here are 25 examples of words and phrases you may be getting mixed up in your writing. Almost all of these items were taken from The Hodges Harbrace Handbook, an excellent resource for beginning and advanced writers alike. Be sure to check it out if you can! Write wisely!

1) accept/except

It’s easy to confuse these words because they sound so similar, but they have very different definitions. “Accept” is a verb that means “to receive with consent”; “except” is a preposition that means “other than”. “Except” is also a verb meaning “to exclude”.

I accept all apologies, except those that aren’t heartfelt.

2) affect/effect

These words are so easy to mix up that I always stop and double-check if I’m using the right one before I move on. “Affect” is a verb meaning “to make a difference to”; “effect” is a noun meaning “result of a cause”. As a verb, “effect” means “to cause”.

The effect that book had on my friend’s life did not affect my opinion of it.

3) among/between

Here’s an example of two words that seem similar in meaning, but that aren’t usually interchangeable because their uses depend on context. Generally speaking, “between” is exclusively for referring to two entities, while three or more should be referred to using “among”.

Between the two of us, I don’t see any love among the three band members.

4) anymore/any more

Who among us hasn’t once mistakenly inserted a space where it wasn’t necessary (or omitted one where it was)? I’m sure we’ve all had our doubts about the difference between “anymore” and “any more”. As one word, “anymore” means “any longer”, while as two, “any more” is used with a negative to mean “no more”.

Do not give me any more problems, or I won’t have the patience to deal with you anymore.

5) can/may

Did anyone else’s parents use to answer the question “Can I?” with “You can, but you may not”? No? Just mine? OK, then. Basically, by answering sarcastically, my parents were teaching us the proper way to ask if we were allowed to do something, as “can” refers to ability while “may” refers to permission.

You can drive 80 miles an hour, but you may not go over the speed limit.

6) coarse/course

Here’s a pair of homophones that are especially easy to get confused because they only differ by one letter. “Coarse” is an adjective that means “rough”, but “course” is a noun that means “route” or “plan of study” (or a verb that means “move without obstruction”).

We’ll need a new course of action if we want to make this coarse piece smooth.

7) complement/compliment

This is another pair of words that sound alike and differ by one letter. Don’t let these verbs confuse you, though. “Complement” means “to complete”, and “compliment” means “to express praise”. Be sure to check which letter you’re using!

I had to compliment her on how well her piece was able to complement mine.

8) elicit/illicit

This mistake is a little less common, but still possible to make due to similar spelling. “Elicit” is a verb meaning “to evoke a response”, and “illicit” is an adjective meaning “illegal”.

She was quick to elicit objections from her peers by talking about her boyfriend’s illicit actions.

9) eminent/imminent

I’ve actually never made this mistake myself because I’m not too familiar with the word “eminent”, but I still think it’s worth mentioning. Though both are adjectives, “eminent” means “distinguished”, and “imminent” means “about to happen”.

For such an eminent artist, worldwide success was imminent.

10) everyday/every day

Oh, those darn spaces, always confusing us! Here’s another mistake we have to watch for, because a single space does change the meaning behind the words! “Everyday” as one word means “commonplace” or “routine”, but “every day” as two words means “each day”.

Every day, I have to help my sister deal with her everyday problems.

11) explicit/implicit

This one might not be very common, but it’s still an important mistake to note, because even though these two adjectives seem similar, they have opposite meanings. “Explicit” means “stated clearly”, while “implicit” means “expressed indirectly”. Make sure you’re not saying the opposite of what you mean!

By using explicit details, the director makes the message of the movie implicit.

12) farther/further

These adverbs may seem interchangeable, but which one you should use actually depends on context. Both are comparatives of “far”, but “farther” is used to refer to geographic distance, while “further” is used to mean “more”.

We’ll need further assistance if we’re to travel farther tomorrow than we did today.

13) fewer/less

I added this example to the list because it’s common for writers to go straight for “less” when indicating lower amounts. Like the cases of “among”/”between” and “farther”/”further”, however, context is important. Though both words mean the same thing, “fewer” is for nouns that can be counted, while “less” is for nouns that can’t.

Since I started outlining my novel, I have fewer blank notebook pages and much less free space on my desk.

14) good/well

Colloquial speech has made it very common for people to mix up the proper uses of “good” and “well”. I can attest to this from personal experience; knowing the difference between “good” and “well” doesn’t keep me from answering “How are you?” with “Good”. But even though they mean the same thing, there’s a difference: “good” is an adjective and “well” is an adverb. Make sure you aren’t confusing them!

A good writer knows how to tell stories well.

15) its/it’s

What’s a list of common grammar mistakes without a few examples of “contraction confusion”? We’ve all been guilty of this error before, but it’s understandable when one apostrophe makes all the difference. “Its” is the possessive form of “it”, and “it’s” is the contraction of “it is”. Careful with that apostrophe!

It’s easy for students to struggle with English and its many grammar rules.

16) lay/lie

This is one mistake I always have to take extra care not to make, because the past tense of one is the present tense of the other! The main difference between these verbs is that one takes an object while the other doesn’t. “Lay” means “to put (something) down”; “lie” means “to rest”.

I have to lay my things on the desk before I can lie down.

17) raise/rise

This is a tough mistake to make, but I’m fairly certain I’ve seen it happen before. Like the previous example, the difference between these verbs is that one is transitive and the other is intransitive. “Raise” means “to lift (something) up”, while “rise” means “to ascend”.

The teacher made me raise my hand and ask permission before I could rise from my chair.

18) sometime/some time

Yes, it’s another case involving a space (sorry for the lame rhyme). Whether you write it as one word or two will alter the meaning of the sentence. “Sometime” as one word means “at an unspecified time”, and “some time” as two words indicates a span of time.

Sometime next month, we’ll be able to spend some time together.

19) than/then

These are two words that I constantly mix up by accident, to the point where I always read the sentence at least three times to make sure I used the right one before moving on. “Than” is a conjunction and preposition used in comparisons; “then” is an adverb indicating a time sequence. Always be sure to double-check!

Back then, he used to say he’d rather listen to underground rock than mainstream pop music.

20) their/there/they’re

Here it is: the famous trio! You didn’t think I’d leave this one out, did you? Self-proclaimed “Internet grammar police” love picking on people for this mistake, and although I sympathize with those who commit the error once in a while, I can’t forgive those who insist on interchanging these words without any respect for the English language. “Their” is the possessive form of “they”; “there” is an adverb referring to location; and “they’re” is the contraction of “they are”. Be careful with your word choice!

They’re going there to retrieve their test scores.

21) to/too/two

Here’s another famous word trio. When one letter makes all the difference, it’s very easy to mix these words up. “To” is a preposition and infinitive marker; “too” is an adverb meaning “also” or “excessively”; and “two” is a number.

Two mistakes in your essay are still too many if you hope to ace this test.

22) weather/whether

This one may seem unlikely, but I swear I’ve seen writers mix up these words before. “Weather” is a noun referring to the state of the atmosphere (and sometimes a verb meaning “to wear away”); “whether” is a conjunction indicating a choice between alternatives. Make sure you’re using the right word!

Whether or not you believe in climate change, you can’t deny that the weather has been strange lately.

23) who/whom

We all know that person who insists on correcting us when we use “who” incorrectly (my family does for sure, because it’s me). Which word you use depends on voice: “who” is used as a subject, while “whom” is used as an object. When in doubt, try rewording the phrase with “he/she” (subject) or “him/her” (object).

To whom it may concern, I’m the one who let the birds out of the cage.

24) whose/who’s

Speaking of “who”, here’s another pair of homophones that are easy to confuse. Even I sometimes have to go back and fix the mistake. “Whose” is the possessive form of “who”, and “who’s” is the contraction of “who is”.

Whose fault is it if we can’t figure out who’s responsible for this mess?

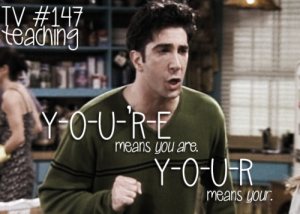

25) your/you’re

And now for the final pair of easily confused words: the famous “your” and “you’re”. Friends fans, remember that moment when Ross is fighting with Rachel over the letter she wrote him, and points out her grammar error for good measure? Yes, he was drawing attention to a mistake that many people are guilty of making at least once in their writing. But we all know which word is which: “your” is the possessive form of “you”, and “you’re” is the contraction of “you are”. The trick is making sure we’re using the right one!

You’re not going anywhere until your homework is done!

These are just some of the many examples of easily confused words in the English language. Yes, an innocent mistake now and then is forgivable; our grammar is so complex that even native speakers struggle with it from time to time. Still, as writers, we should take care to avoid these mistakes as much as possible. If nothing else, we should be setting a good example for all other English speakers!

What about you? Have you ever confused any of these words and phrases before? What other examples would you add to this list?

by Naomi L. | October 23, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Featured |

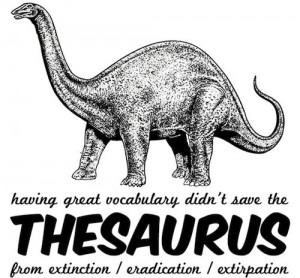

Remember the elementary school days when our teachers introduced us to those trusty reference books that would guide us through our writing? These were the friends we would come to rely on for the rest of our lives, the books containing so many of the answers we would need to survive our school years. The dictionary told us what those long words we’d never seen before meant. The atlas helped us find those faraway places we’d heard about in Geography class. There were encyclopedias and almanacs full of facts that came in handy for homework assignments. And then there was that book that gave us lists of synonyms and antonyms for the words we wanted to use in our writing: the thesaurus.

This last book is an interesting case, though, because unlike the others, it has the same potential to hinder as it does to help. Yes, the thesaurus is a top go-to resource for many writers, especially beginners looking to enhance their work. However, something our teachers may have neglected to tell us is that the guide comes with unwritten instructions: use knowledgeably.

Trustworthy/reliable friend/ally?

“Hooray yay for synonyms!”

(Screenshot from RubberNinja‘s Gameoverse videos)

When we were first introduced to the thesaurus, we were taught that it’s a great resource for helping to expand our vocabulary, and that’s true. I can’t even count how many new words I’ve learned just by looking up synonyms for ones I already knew. Every time I work on my stories, I have my dictionary/thesaurus widget handy to help me find replacements for words that would otherwise be repeated too soon in the narrative. It even helps me remember advanced vocabulary that I may have forgotten (which happens more often than I’d normally care to admit).

A good use of a thesaurus is as a reverse dictionary. You know how sometimes you know exactly what you mean to say, but you just can’t find the right word for it? Well, all you have to do is look up more common words for the definition you want and see what options come up. True, this method may not be as effective as using an actual reverse dictionary, which has full definitions and cross referencing, but it’s still a convenient alternative to find simpler examples, especially for writers who don’t have access to a more complete guide.

So yes, writers, the thesaurus is your friend. It will save you from plain and repetitive writing, and can teach you a thing or two (or ten) in the vocabulary department. But be warned, because placing too much trust in this guide can have negative consequences as well…

Or dubious/suspicious enemy/foe?

So how could this dependable friend of ours also be a hazard to our writing? Instead of launching into a dissertation about the dangers of overusing a thesaurus, allow me to illustrate the point instead with an example from the popular TV series Friends. In this episode, Joey wants to write a letter of recommendation for Monica and Chandler, who are planning to adopt. When he mentions that he wants to make it sound smart, Ross suggests he use a thesaurus to replace plain words with advanced ones. Unfortunately, the results are less than satisfactory…

Joey: Hey, finished my recommendation. (hands a letter to Chandler and Monica) Here. And I think you’ll be very, very happy.

[…]

Chandler: I don’t, uh, understand.

Joey: Some of the words a little too sophisticated for ya?

Monica: It doesn’t make any sense.

Joey: Of course it does! It’s smart! I used a the-saurus!

Chandler: On every word?

Joey: Yep.

Monica: All right, what was this sentence originally?

Joey: Oh, “They are warm, nice people with big hearts”.

Chandler: And that became “They are humid, prepossessing Homo sapiens with full-sized aortic pumps”?

Joey: Yeah, yeah. And hey, I really mean it, dude.

– Friends (Season 10, Episode 5 – The One Where Rachel’s Sister Babysits)

As you can see, Joey’s overuse of a thesaurus causes him to turn out a ridiculous stream of long words that have nothing to do with what he wants to say. While Ross’s advice may have been good in theory, he probably should have warned Joey not to go straight for the “smartest sounding” word every single time. The problem wasn’t just that his letter would come out overly “purple“, but that there was an important tip he neglected to keep in mind when choosing synonyms: context is key.

A notable example of a misused synonym in the above dialogue is “humid”. As we all know, while “warm” and “humid” have comparable definitions when it comes to describing the weather, only “warm” is also applicable to people. A similar problem happens with the use of Homo sapiens, which is only good for scientific writing and doesn’t really work as an alternative for “people”. With all these big words so out of place, it’s no wonder Monica and Chandler couldn’t understand anything Joey had written!

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the full definition of a word before you try to pass it off as a replacement for a more common one, advice that many writers fail to take into account.

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the full definition of a word before you try to pass it off as a replacement for a more common one, advice that many writers fail to take into account.

One particularly embarrassing example of this practice from my own experience is when I used the word “fortuitous” incorrectly in a story. My thesaurus listed it as a synonym for “random”, but what I didn’t realize until after publishing the piece was that while “random” is a neutral word, “fortuitous” usually has a positive connotation (as in “good fortune”), which was not the feeling I intended to convey. Fortunately, no one ever called me out on it, but it was still embarrassing to know the mistake was out there for anyone to see. So to be safe, make sure you look up the definition of a synonym before you use it in your writing. You’ll be glad you did.

A thesaurus can be a friend or an enemy, depending on how much faith a writer is willing to invest in it. While its uses are mostly beneficial, it’s up to you to make sure that this trusted ally doesn’t turn on you and muddle up the meaning behind your words. It’s OK to trust your thesaurus to help you enhance the vocabulary in your writing. Just try not to use it in excess!

Monica: Hey, Joey, I don’t think we can use this.

Joey: Why not?

Monica: Well, because you signed it “Baby Kangaroo Tribbiani”.

What about you? Do you make good use of your thesaurus? Has it been more of a help or a hazard to your writing?

by Naomi L. | September 18, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Writer's Toolkit |

Who among us writers hasn’t found themselves doubting at one time or another whether the grammar in our writing was correct? I myself have at least three doubts regarding the previous sentence in this paragraph! We’ve probably all been in this situation before, getting stuck during the editing process over a comma we weren’t sure was correctly placed or the appropriate formatting for a citation. That’s why today’s Writer’s Toolkit review features a nifty handbook designed to aid writers through the trials of editing and revision: The Hodges Harbrace Handbook by Cheryl Glenn and Loretta Gray.

Book Summary

This handbook was one of the required materials for the online creative writing course I took through UC Berkeley. I currently own the 17th edition, published in 2009 with an MLA update, though at the time of writing this review, an 18th edition has already been released (and you can be sure that more will follow).

Originally published in 1941 by English professor John Hodges as the Harbrace Handbook of English, this book has since evolved into one of the richest English writing resources available today. The contents are organized into seven parts:

- Grammar

- Mechanics

- Punctuation

- Spelling and Diction

- Effective Sentences

- Writing

- Research and Documentation

Parts are subdivided into chapters and color-coded for your convenience (sorry, I couldn’t resist). Also included are a preface by the authors outlining new features and revisions for the current edition, a glossary of usage, a glossary of frequently used terms, and an index.

Pros

The first thing one might notice upon opening The Hodges Harbrace Handbook is the table of contents printed right into the back of the front cover and the first pages. At a glance, it’s clear how thorough this manual is, covering as many topics as possible from grammar and mechanics to proper usage of English in college-level writing. The table provides a quick guide to different sections and chapters, which are colored and numbered for easy reference.

As for the actual content, I find the explanations easy to understand, bearing in mind that the book is geared toward college students and above. To add to the educational experience, practice exercises are included within chapters, as are checklists for certain cases that come up in the editing process. Other notable features are the special boxes interspersed throughout the book: “Thinking Rhetorically” invites writers to consider the impact of their writing choices on their target audience; “Multilingual Writers” notes common areas of confusion for English learners, especially those for whom English is not a first language; and “Tech Savvy” provides helpful tips for using word-processing software, a useful feature for writers of the digital age. The last pages of the handbook include indexes for “Multilingual Writers” boxes, checklists and revision symbols.

One of my favorite details about the most recent editions of The Hodges Harbrace Handbook is the update for writers of modern times. As of the 17th edition, a new chapter titled “Online Writing” is included in the “Writing” part of the guide, and revisions reflect updates to MLA and APA guidelines and an expansion to a chapter on using writing software for business. Because of these updates, I would strongly advise against purchasing any edition of this handbook earlier than the 17th, published in 2009.

Cons

Honestly, this list is pretty short. In fact, the first issue I found with this handbook may have been due to error on my part. There were a couple of questions for which I couldn’t find answers in the handbook, either because I was searching for them in the wrong chapters or because they simply weren’t there. Also, the preface mentions some supplemental materials that are only available when bundled with the handbook at an additional cost. Not exactly a downside, but just a point to keep in mind if you’re looking for a complete learning experience to go with this guide.

Oh, and of course there’s the matter of price. A new latest-edition hard copy goes for over $80 on Amazon, which may seem steep to a student who only plans on using it for a semester. On the other hand, a prolific writer who needs to constantly edit and revise their work would probably find any price under $100 quite reasonable. As with any product, it’s all a matter of whether or not you feel you’d be able to get your money’s worth out of it.

Summary

Pros

- Versatile and thorough guide to the English language

- Well-organized contents

- Easy to understand

- In-chapter practice exercises

- Special boxes for “Thinking Rhetorically”, “Multilingual Writers” and “Tech Savvy” tips

- Extra indexes for “Multilingual Writers”, checklists and revision symbols

- Updated edition for writing in the modern age

Cons

- Possible missing information

- Supplemental materials available at additional cost

- Price ($80+ new on Amazon)

Conclusion

I highly recommend this handbook to any writer who puts as much effort into editing as into writing, if not more. Though I purchased my copy as a requirement for a class two years ago, I have since found it quite helpful when revising my work, and continue to use it today. Whether you’re looking for a complete guide to basic grammar or a full learning experience in the English language, The Hodges Harbrace Handbook is a great resource to keep handy, as much for the student writing for college as for the creative individual writing for life.

by Naomi L. | June 26, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing |

I don’t usually like to get picky about grammar, save for when I’m editing my own writing (or teasing my closest friends). Every now and then, however, I catch a few minor “mistakes” in the writing and speech of others that jump out at me. I use quotation marks because they aren’t necessarily wrong; I just tend to find them a bit odd, and occasionally a little annoying. Maybe there are others who would agree, and maybe sometimes it’s just me being my regular nerdy self.

I don’t usually like to get picky about grammar, save for when I’m editing my own writing (or teasing my closest friends). Every now and then, however, I catch a few minor “mistakes” in the writing and speech of others that jump out at me. I use quotation marks because they aren’t necessarily wrong; I just tend to find them a bit odd, and occasionally a little annoying. Maybe there are others who would agree, and maybe sometimes it’s just me being my regular nerdy self.

Just for fun, today’s topic brings you three random “pet peeves” of mine that are widely accepted as understandable language. You can decide for yourself where you stand on these…

1) When “could” really means “couldn’t”

I admit that it bothers me a little to see people using the phrase “I could care less” when they clearly mean to say “I couldn’t care less”. The logic behind the phrasing is simple: if you “couldn’t care less”, you’ve reached the limit of how little you can care about something, whereas if you “could care less”, there’s still a little part of you that does care and has yet to be eliminated.

I’ve heard a couple of theories as to how the “could” variation emerged in colloquial speech. One states that it was originally meant to be used in a sarcastic manner and not taken literally. Another explanation, according to American linguist Atcheson L. Hench, is that slurred speech has garbled the “couldn’t” of the correct phrase into the “could” that most people hear (American Speech, 159; 1973).

Which explanation is the truth? I have no idea. All I know is that I always use the original phrasing in my own speech, and if anyone doesn’t believe me when I say it’s the “correct” form, I couldn’t care less.

2) The American pronunciation of “niche”

I’ve lost count of all the playful arguments I’ve had with my best friend over this word. Our debates usually play out the same: I tell him the correct pronunciation is “neesh”; he answers back that people say “nitch”. I explain that the word comes from French, so its original pronunciation should be maintained; he argues that we’re American and we should adapt to the way most Americans speak. I ask him if by that logic, we should also start saying “ba-LET” and “gor-MET”; he claims that’s not the same thing because everyone says “ba-LAY” and “gor-MAY” without a problem. Then we toss the word “niche” back and forth, each of us insisting that our pronunciation is correct, until we both get tired and agree to disagree before changing the subject. After the entire discussion is over, we’re still friends.

Albeit friends who each still think they’re right. (Neesh.)

3) The alternative spelling of “doughnut”

To be fair, this one is more of a personal preference than an actual pet peeve. I understand that both “doughnut” and “donut” are equally acceptable spellings; I just prefer the former because it seems to me – for lack of a better description – “more correct”. It is the original spelling, after all; the invention of doughnuts can be traced back as far as the 19th century, but the earliest known printed use of the word “donut” is only from 1900 (Peck’s Bad Boy and His Pa by George W. Peck). Not to mention, “doughnut” also feels more complete: just by looking at the word, you can already tell what the main ingredient is…

Still, both spellings are equally pervasive in American English, though “doughnut” seems to be the more common form outside of the United States. Oxford Dictionaries list “donut” as the alternative spelling of “doughnut”, making the longer word the traditional option for more formal writing, yet the shortened form is popular for references like company names (e.g. Dunkin’ Donuts). Even my best friend (yes, the same young man who advocates so strongly for “nitch”) insists that “donut” is the best spelling because it’s modern, and thus more appealing to the readers of today. As he says whenever I insist that “doughnut” is the better choice, “Take it up with The Donut Man!”

These are just a few random examples of minor deviations from my grammatical standards. Like I said, they aren’t really wrong; it’s all a matter of preference. And call me a geek if you like, but I simply chose the alternatives that I deemed grammatically correct.

So what about you? Can you relate to any of the examples listed above? Do you have pet peeves of your own that don’t really detract from communication more than they just annoy you?

OK, I know people aren’t really trying to say “axe” in this context, but the common mispronunciation of the word “ask” still bothers me enough to warrant a place on this list. I admit that I cringe a little whenever I hear someone say they want to “aks” a question; every time, the editor in my head screams “Ask! Ask! ASK!” Yes, I understand that people in different regions have different ways of speaking, and old habits are hard to break. But that doesn’t make this mistake OK.

OK, I know people aren’t really trying to say “axe” in this context, but the common mispronunciation of the word “ask” still bothers me enough to warrant a place on this list. I admit that I cringe a little whenever I hear someone say they want to “aks” a question; every time, the editor in my head screams “Ask! Ask! ASK!” Yes, I understand that people in different regions have different ways of speaking, and old habits are hard to break. But that doesn’t make this mistake OK.

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the

Recent Comments