by Naomi L. | November 6, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing |

All native English speakers are familiar with this problem: words and phrases that appear similar in spelling, pronunciation or meaning, but that actually have distinct definitions. This, of course, can cause some confusion when writing. After all, it’s not always easy keeping track of the right words for the context we want, and even the most proficient writers make mistakes. But nobody’s perfect, right?

To help you avoid some common (and a few uncommon) grammar pitfalls, here are 25 examples of words and phrases you may be getting mixed up in your writing. Almost all of these items were taken from The Hodges Harbrace Handbook, an excellent resource for beginning and advanced writers alike. Be sure to check it out if you can! Write wisely!

To help you avoid some common (and a few uncommon) grammar pitfalls, here are 25 examples of words and phrases you may be getting mixed up in your writing. Almost all of these items were taken from The Hodges Harbrace Handbook, an excellent resource for beginning and advanced writers alike. Be sure to check it out if you can! Write wisely!

1) accept/except

It’s easy to confuse these words because they sound so similar, but they have very different definitions. “Accept” is a verb that means “to receive with consent”; “except” is a preposition that means “other than”. “Except” is also a verb meaning “to exclude”.

I accept all apologies, except those that aren’t heartfelt.

2) affect/effect

These words are so easy to mix up that I always stop and double-check if I’m using the right one before I move on. “Affect” is a verb meaning “to make a difference to”; “effect” is a noun meaning “result of a cause”. As a verb, “effect” means “to cause”.

The effect that book had on my friend’s life did not affect my opinion of it.

3) among/between

Here’s an example of two words that seem similar in meaning, but that aren’t usually interchangeable because their uses depend on context. Generally speaking, “between” is exclusively for referring to two entities, while three or more should be referred to using “among”.

Between the two of us, I don’t see any love among the three band members.

4) anymore/any more

Who among us hasn’t once mistakenly inserted a space where it wasn’t necessary (or omitted one where it was)? I’m sure we’ve all had our doubts about the difference between “anymore” and “any more”. As one word, “anymore” means “any longer”, while as two, “any more” is used with a negative to mean “no more”.

Do not give me any more problems, or I won’t have the patience to deal with you anymore.

5) can/may

Did anyone else’s parents use to answer the question “Can I?” with “You can, but you may not”? No? Just mine? OK, then. Basically, by answering sarcastically, my parents were teaching us the proper way to ask if we were allowed to do something, as “can” refers to ability while “may” refers to permission.

You can drive 80 miles an hour, but you may not go over the speed limit.

6) coarse/course

Here’s a pair of homophones that are especially easy to get confused because they only differ by one letter. “Coarse” is an adjective that means “rough”, but “course” is a noun that means “route” or “plan of study” (or a verb that means “move without obstruction”).

We’ll need a new course of action if we want to make this coarse piece smooth.

7) complement/compliment

This is another pair of words that sound alike and differ by one letter. Don’t let these verbs confuse you, though. “Complement” means “to complete”, and “compliment” means “to express praise”. Be sure to check which letter you’re using!

I had to compliment her on how well her piece was able to complement mine.

8) elicit/illicit

This mistake is a little less common, but still possible to make due to similar spelling. “Elicit” is a verb meaning “to evoke a response”, and “illicit” is an adjective meaning “illegal”.

She was quick to elicit objections from her peers by talking about her boyfriend’s illicit actions.

9) eminent/imminent

I’ve actually never made this mistake myself because I’m not too familiar with the word “eminent”, but I still think it’s worth mentioning. Though both are adjectives, “eminent” means “distinguished”, and “imminent” means “about to happen”.

For such an eminent artist, worldwide success was imminent.

10) everyday/every day

Oh, those darn spaces, always confusing us! Here’s another mistake we have to watch for, because a single space does change the meaning behind the words! “Everyday” as one word means “commonplace” or “routine”, but “every day” as two words means “each day”.

Every day, I have to help my sister deal with her everyday problems.

11) explicit/implicit

This one might not be very common, but it’s still an important mistake to note, because even though these two adjectives seem similar, they have opposite meanings. “Explicit” means “stated clearly”, while “implicit” means “expressed indirectly”. Make sure you’re not saying the opposite of what you mean!

By using explicit details, the director makes the message of the movie implicit.

12) farther/further

These adverbs may seem interchangeable, but which one you should use actually depends on context. Both are comparatives of “far”, but “farther” is used to refer to geographic distance, while “further” is used to mean “more”.

We’ll need further assistance if we’re to travel farther tomorrow than we did today.

13) fewer/less

I added this example to the list because it’s common for writers to go straight for “less” when indicating lower amounts. Like the cases of “among”/”between” and “farther”/”further”, however, context is important. Though both words mean the same thing, “fewer” is for nouns that can be counted, while “less” is for nouns that can’t.

Since I started outlining my novel, I have fewer blank notebook pages and much less free space on my desk.

14) good/well

Colloquial speech has made it very common for people to mix up the proper uses of “good” and “well”. I can attest to this from personal experience; knowing the difference between “good” and “well” doesn’t keep me from answering “How are you?” with “Good”. But even though they mean the same thing, there’s a difference: “good” is an adjective and “well” is an adverb. Make sure you aren’t confusing them!

A good writer knows how to tell stories well.

15) its/it’s

What’s a list of common grammar mistakes without a few examples of “contraction confusion”? We’ve all been guilty of this error before, but it’s understandable when one apostrophe makes all the difference. “Its” is the possessive form of “it”, and “it’s” is the contraction of “it is”. Careful with that apostrophe!

It’s easy for students to struggle with English and its many grammar rules.

16) lay/lie

This is one mistake I always have to take extra care not to make, because the past tense of one is the present tense of the other! The main difference between these verbs is that one takes an object while the other doesn’t. “Lay” means “to put (something) down”; “lie” means “to rest”.

I have to lay my things on the desk before I can lie down.

17) raise/rise

This is a tough mistake to make, but I’m fairly certain I’ve seen it happen before. Like the previous example, the difference between these verbs is that one is transitive and the other is intransitive. “Raise” means “to lift (something) up”, while “rise” means “to ascend”.

The teacher made me raise my hand and ask permission before I could rise from my chair.

18) sometime/some time

Yes, it’s another case involving a space (sorry for the lame rhyme). Whether you write it as one word or two will alter the meaning of the sentence. “Sometime” as one word means “at an unspecified time”, and “some time” as two words indicates a span of time.

Sometime next month, we’ll be able to spend some time together.

19) than/then

These are two words that I constantly mix up by accident, to the point where I always read the sentence at least three times to make sure I used the right one before moving on. “Than” is a conjunction and preposition used in comparisons; “then” is an adverb indicating a time sequence. Always be sure to double-check!

Back then, he used to say he’d rather listen to underground rock than mainstream pop music.

20) their/there/they’re

Here it is: the famous trio! You didn’t think I’d leave this one out, did you? Self-proclaimed “Internet grammar police” love picking on people for this mistake, and although I sympathize with those who commit the error once in a while, I can’t forgive those who insist on interchanging these words without any respect for the English language. “Their” is the possessive form of “they”; “there” is an adverb referring to location; and “they’re” is the contraction of “they are”. Be careful with your word choice!

They’re going there to retrieve their test scores.

21) to/too/two

Here’s another famous word trio. When one letter makes all the difference, it’s very easy to mix these words up. “To” is a preposition and infinitive marker; “too” is an adverb meaning “also” or “excessively”; and “two” is a number.

Two mistakes in your essay are still too many if you hope to ace this test.

22) weather/whether

This one may seem unlikely, but I swear I’ve seen writers mix up these words before. “Weather” is a noun referring to the state of the atmosphere (and sometimes a verb meaning “to wear away”); “whether” is a conjunction indicating a choice between alternatives. Make sure you’re using the right word!

Whether or not you believe in climate change, you can’t deny that the weather has been strange lately.

23) who/whom

We all know that person who insists on correcting us when we use “who” incorrectly (my family does for sure, because it’s me). Which word you use depends on voice: “who” is used as a subject, while “whom” is used as an object. When in doubt, try rewording the phrase with “he/she” (subject) or “him/her” (object).

To whom it may concern, I’m the one who let the birds out of the cage.

24) whose/who’s

Speaking of “who”, here’s another pair of homophones that are easy to confuse. Even I sometimes have to go back and fix the mistake. “Whose” is the possessive form of “who”, and “who’s” is the contraction of “who is”.

Whose fault is it if we can’t figure out who’s responsible for this mess?

25) your/you’re

And now for the final pair of easily confused words: the famous “your” and “you’re”. Friends fans, remember that moment when Ross is fighting with Rachel over the letter she wrote him, and points out her grammar error for good measure? Yes, he was drawing attention to a mistake that many people are guilty of making at least once in their writing. But we all know which word is which: “your” is the possessive form of “you”, and “you’re” is the contraction of “you are”. The trick is making sure we’re using the right one!

You’re not going anywhere until your homework is done!

These are just some of the many examples of easily confused words in the English language. Yes, an innocent mistake now and then is forgivable; our grammar is so complex that even native speakers struggle with it from time to time. Still, as writers, we should take care to avoid these mistakes as much as possible. If nothing else, we should be setting a good example for all other English speakers!

What about you? Have you ever confused any of these words and phrases before? What other examples would you add to this list?

by Naomi L. | October 23, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Featured |

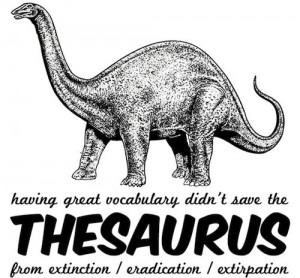

Remember the elementary school days when our teachers introduced us to those trusty reference books that would guide us through our writing? These were the friends we would come to rely on for the rest of our lives, the books containing so many of the answers we would need to survive our school years. The dictionary told us what those long words we’d never seen before meant. The atlas helped us find those faraway places we’d heard about in Geography class. There were encyclopedias and almanacs full of facts that came in handy for homework assignments. And then there was that book that gave us lists of synonyms and antonyms for the words we wanted to use in our writing: the thesaurus.

This last book is an interesting case, though, because unlike the others, it has the same potential to hinder as it does to help. Yes, the thesaurus is a top go-to resource for many writers, especially beginners looking to enhance their work. However, something our teachers may have neglected to tell us is that the guide comes with unwritten instructions: use knowledgeably.

Trustworthy/reliable friend/ally?

“Hooray yay for synonyms!”

(Screenshot from RubberNinja‘s Gameoverse videos)

When we were first introduced to the thesaurus, we were taught that it’s a great resource for helping to expand our vocabulary, and that’s true. I can’t even count how many new words I’ve learned just by looking up synonyms for ones I already knew. Every time I work on my stories, I have my dictionary/thesaurus widget handy to help me find replacements for words that would otherwise be repeated too soon in the narrative. It even helps me remember advanced vocabulary that I may have forgotten (which happens more often than I’d normally care to admit).

A good use of a thesaurus is as a reverse dictionary. You know how sometimes you know exactly what you mean to say, but you just can’t find the right word for it? Well, all you have to do is look up more common words for the definition you want and see what options come up. True, this method may not be as effective as using an actual reverse dictionary, which has full definitions and cross referencing, but it’s still a convenient alternative to find simpler examples, especially for writers who don’t have access to a more complete guide.

So yes, writers, the thesaurus is your friend. It will save you from plain and repetitive writing, and can teach you a thing or two (or ten) in the vocabulary department. But be warned, because placing too much trust in this guide can have negative consequences as well…

Or dubious/suspicious enemy/foe?

So how could this dependable friend of ours also be a hazard to our writing? Instead of launching into a dissertation about the dangers of overusing a thesaurus, allow me to illustrate the point instead with an example from the popular TV series Friends. In this episode, Joey wants to write a letter of recommendation for Monica and Chandler, who are planning to adopt. When he mentions that he wants to make it sound smart, Ross suggests he use a thesaurus to replace plain words with advanced ones. Unfortunately, the results are less than satisfactory…

Joey: Hey, finished my recommendation. (hands a letter to Chandler and Monica) Here. And I think you’ll be very, very happy.

[…]

Chandler: I don’t, uh, understand.

Joey: Some of the words a little too sophisticated for ya?

Monica: It doesn’t make any sense.

Joey: Of course it does! It’s smart! I used a the-saurus!

Chandler: On every word?

Joey: Yep.

Monica: All right, what was this sentence originally?

Joey: Oh, “They are warm, nice people with big hearts”.

Chandler: And that became “They are humid, prepossessing Homo sapiens with full-sized aortic pumps”?

Joey: Yeah, yeah. And hey, I really mean it, dude.

– Friends (Season 10, Episode 5 – The One Where Rachel’s Sister Babysits)

As you can see, Joey’s overuse of a thesaurus causes him to turn out a ridiculous stream of long words that have nothing to do with what he wants to say. While Ross’s advice may have been good in theory, he probably should have warned Joey not to go straight for the “smartest sounding” word every single time. The problem wasn’t just that his letter would come out overly “purple“, but that there was an important tip he neglected to keep in mind when choosing synonyms: context is key.

A notable example of a misused synonym in the above dialogue is “humid”. As we all know, while “warm” and “humid” have comparable definitions when it comes to describing the weather, only “warm” is also applicable to people. A similar problem happens with the use of Homo sapiens, which is only good for scientific writing and doesn’t really work as an alternative for “people”. With all these big words so out of place, it’s no wonder Monica and Chandler couldn’t understand anything Joey had written!

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the full definition of a word before you try to pass it off as a replacement for a more common one, advice that many writers fail to take into account.

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the full definition of a word before you try to pass it off as a replacement for a more common one, advice that many writers fail to take into account.

One particularly embarrassing example of this practice from my own experience is when I used the word “fortuitous” incorrectly in a story. My thesaurus listed it as a synonym for “random”, but what I didn’t realize until after publishing the piece was that while “random” is a neutral word, “fortuitous” usually has a positive connotation (as in “good fortune”), which was not the feeling I intended to convey. Fortunately, no one ever called me out on it, but it was still embarrassing to know the mistake was out there for anyone to see. So to be safe, make sure you look up the definition of a synonym before you use it in your writing. You’ll be glad you did.

A thesaurus can be a friend or an enemy, depending on how much faith a writer is willing to invest in it. While its uses are mostly beneficial, it’s up to you to make sure that this trusted ally doesn’t turn on you and muddle up the meaning behind your words. It’s OK to trust your thesaurus to help you enhance the vocabulary in your writing. Just try not to use it in excess!

Monica: Hey, Joey, I don’t think we can use this.

Joey: Why not?

Monica: Well, because you signed it “Baby Kangaroo Tribbiani”.

What about you? Do you make good use of your thesaurus? Has it been more of a help or a hazard to your writing?

by Naomi L. | July 24, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Featured, Tropes |

I’m polymerized tree sap and you’re an inorganic adhesive, so whatever verbal projectile you launch in my direction is reflected off of me, returns on its original trajectory, and adheres to you.

– Dr. Sheldon Cooper, The Big Bang Theory (Season 1, Episode 13 – The Bat Jar Conjecture)

Fans of the comedy TV series The Big Bang Theory likely remember this quote from the Physics Bowl episode, when Sheldon reacts to an insult from fellow physicist Leslie Winkle by saying as condescendingly as possible that “he is rubber and she is glue”. However, the fact that he seems to go out of his way to use the most advanced vocabulary possible in his retort only adds to the hilarious running gag of Leslie always managing to beat her rival at a game of wits.

So what lesson should novice writers be learning from Sheldon’s backfired comment? That trying too hard to sound smart often has the opposite effect than what you might expect, that is, it hurts more than it helps.

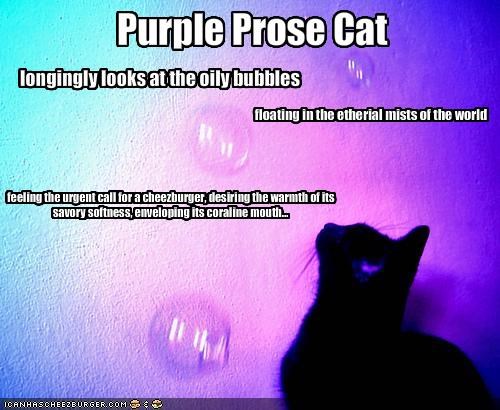

What is this amethystine composition of which you speak?

Writing that is overly decorated with fancy words and elaborate details is known as “purple prose”. It’s an especially common practice among inexperienced writers, who often believe that to write a really good story (or improve upon an existing dull one), one needs to dress up the prose with as many big words as possible to make their work look sophisticated. Basically, beginners seem to have this grand illusion that great literature is that which stands above the level of everyday speech.

Purple prose: Contemplate this exquisite aubergine blossom of the Rosaceae family

Everyday speech: Look at this beautiful purple rose

But here’s the problem with that logic: everyday speech is the level where most readers are, and more importantly, where they want to stay. Readers today don’t want to bore their way through long descriptions or have to pause at every other page to look up half the words they just read in the dictionary. They want writing that’s simple, that they can understand and find relatable, similar to the language they use themselves in the real world.

So I’ve been writing erroneously… I mean, wrong all this time?

Calm down, and take a second to note that I said “similar to”, not “the same as”. It’s OK to use some higher-level vocabulary and detailed narration in your stories, for when done in moderation and in tone with the style of the work, these can actually add to the quality of your writing. The danger is using these tools in excess, because after you’ve passed a certain point in flowering up your prose, these details will begin to draw attention to themselves and away from the flow of your story. To sum up, a little is fine, but too much is bad. Write with caution.

Now before anyone accuses me of hypocrisy, allow me the chance to admit to this embarrassing fact: I am guilty of writing purple prose. Even if I don’t always choose the fanciest synonyms I can find to replace everyday words, I love decorating my writing with adjectives and adverbs, and I tend to use intermediate-level words where common ones would work just fine. That being said, I used to be much worse. When I first started writing, I had this idea that nobody would want to read stories written in the plain language of a ten-year-old, so even though I was already well-read for my age, I went out of my way to find “bigger and better” words for my fiction. It wasn’t until I started learning about common writing mistakes as a young adult that I realized how flowery my early writing was, and I’ve since been gradually cutting the bad habits of my childhood. So take it from a writer who’s still breaking out of the novice phase: tone down the purple and focus on writing simple prose. Your readers will appreciate it.

It’s worth noting at this point that as strongly as most experienced writers will argue against this practice, prose style is and always will be subjective. It’s entirely possible for a writer to not only be aware they write such elaborate prose, but actually do it on purpose. So if you’re a beginning writer guilty of this trope, don’t feel bad right off the bat. Maybe your goal is to imitate the exact styles of writers like William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens and Jane Austen, and that’s fine. Just know that unless you’re going for satire, most of the audience who would take your work seriously has probably been dead for a few hundred years.

It’s worth noting at this point that as strongly as most experienced writers will argue against this practice, prose style is and always will be subjective. It’s entirely possible for a writer to not only be aware they write such elaborate prose, but actually do it on purpose. So if you’re a beginning writer guilty of this trope, don’t feel bad right off the bat. Maybe your goal is to imitate the exact styles of writers like William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens and Jane Austen, and that’s fine. Just know that unless you’re going for satire, most of the audience who would take your work seriously has probably been dead for a few hundred years.

But I want to be taken seriously today! What should I do?

Don’t worry, the “purple prose bug” is treatable! For those of you aspiring writers who wish to establish yourselves before you try to follow the great authors who bend the rules, here’s a quick list of common purple prose mistakes and how you can avoid them:

1) Excessive detail. Yes, describing the setting of a scene before the action starts is often essential to telling a good story, but please don’t go on for a dozen pages about the hundred different colors in the sky or the history hidden in every brick of every building. Just because authors like J.R.R. Tolkien and Victor Hugo could get away with it doesn’t mean you can. One paragraph should be enough to set your scene, but no more than two.

2) Overly decorated nouns and verbs. If you’re one of the millions of readers who have read all of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books, you may have learned that nouns and verbs should almost always include a “modifying friend”. But Rowling is an exception, a world-famous author of one of the best-selling book series in history, which you are (probably) not. That means she can do whatever she wants with her writing, whereas you should practice creating basic prose before you work too hard to copy her style. Try not to use too many adjectives and adverbs in your writing. Though this may seem counterintuitive, many famous writers would agree that less is more. If you don’t believe so, read a story by Ernest Hemingway or Mark Twain, and you’ll see how writing can be great without the need for too many “attachments”. To quote Twain, “When you catch an adjective, kill it.”

3) Said bookisms. This is one of the most common mistakes made by beginning writers: the constant use of alternative verbs for the word “said”. There’s a general belief that when it comes to writing dialogue, “said” is too plain and overused, so writers should go out of their way to replace it with words like “asked”, “muttered”, “hissed”, etc. As a teenager, I used a lot of these in my writing; I wouldn’t be surprised if I read back a dialogue-heavy scene from one of my old stories and found at least three pages between consecutive uses of “said”. But even famous authors seem to be guilty of this sometimes (I’m given to understand there’s an entire blog devoted to poking fun at the purpleness of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series), so don’t feel too bad if you find your own writing full of these bookisms. The important thing is that you know you should fix them. Dialogue should convey tone by itself, no extra tags required.

4) Too much “fancy vocabulary”. Continuing from the example of “said”, some writers tend to try and find as many advanced-sounding synonyms as possible to substitute the common words in their stories. While this may be fine once in a while, you shouldn’t run to the thesaurus for every other word you want to write. Otherwise, you’ll end up sending your readers to the dictionary just as frequently. It’s great to learn new words, but think about it for a second: the more time you put into driving your audience to read another book, the less time they’ll spend reading yours. Try to stick to vocabulary that your readers will understand, and if you must throw in a higher-level word now and then, at least have the courtesy to make its definition clear in context.

5) Exaggerated sentiment. There isn’t a lot I can say here except that this is pretty much a writer’s attempt to manipulate the reader into reacting a certain way to their writing. Going back to the first item on the list, if you throw too much rhetorical writing into your stories, it comes across as you trying too hard to evoke specific emotions from your readers, which more often than not will have the opposite effect. Trust your audience to understand what you’re trying to tell them. If you write it plainly enough, they will feel it.

Purple prose is a dangerous habit of many writers, and while it may be OK for some, most should make a point of avoiding or overcoming it, no matter how difficult this seems. If nothing else, choosing to create simple and clean prose is a sign of respect to your work and your readers, so take care with your style of writing. I’m certainly still trying.

So what are your experiences with purple prose? Have you read stories that you found too flowery for your taste? Were you (or are you) ever guilty of making these mistakes yourself?

by Naomi L. | May 29, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing |

I fell in love with creative writing when I was in the fourth grade, after spending many childhood years reading books and discovering the fun of narrative composition assignments in school. At the age of ten, I decided that writing was something I wanted to do for the rest of my life, and publishing a book was one of those goals I absolutely had to accomplish at least once before I died. Eager to get a headstart on my career as an author, I wasted no time in writing my first novel. As it turned out, however, being a preteen writer came with a major disadvantage: a severe lack of experience.

The vintage typewriter of my life: this is the classic iMac on which my very first novel was written.

The final product of my labor was a relatively short tale about a child’s adventure through a dream world, creating imaginary friends along the way to aid her on her quest to develop what she had been missing for years: an active imagination. Though I believed the idea to be a good one, I realized a few years after finishing the story that the execution was subpar due to various mistakes that I hadn’t recognized when I was ten. Of course, I don’t want to bore you with the details of every single one, so instead, here’s a list of five of the most important aspects of fiction writing that I wish I had known when I was working on my first book.

1) Good books don’t get written in a day.

Unless you’re an extremely focused hermit locked in a room with nothing but a desk and a typewriter (or you’re the Flash), you’re not turning out a bestselling novel in less than 24 hours. Now, I didn’t literally expect to write a whole book in one day, but given that the basic outline of a plot was already clear in my mind when I started, I also didn’t expect it to take longer than a week to finish. Instead, I probably spent the equivalent of at least a month’s worth of writing before I finally completed my novel. By creating such unrealistic expectations, I was setting myself up for the disappointment that inevitably hit me after the first week of writing came and went. And disappointment is not an emotion that ten-year-olds are usually prepared to handle well…

It’s worth mentioning, however, that I probably still could have finished my story in less time than it actually took me. So why didn’t I? Because there was one piece of advice I didn’t take into account before I started…

2) Planning is important.

I made the rookie mistake of thinking that a single idea was all I needed before I actually started writing a novel. I thought that as long as I could keep that one idea clear in my head, inspiration would take over and I’d have a full manuscript ready before I knew it. Unfortunately, as I quickly discovered, novels don’t quite work that way. There were several instances during the writing process when I had to stop and even retrace my steps because I wasn’t entirely sure how to move the action forward, or how to fill a gap between two scenes that I already knew were going to happen. I’m not saying I should have spent a year only planning without actually writing anything, but had I taken just a little more time to map out the full course of my story before I dove headfirst into the narrative, I could have saved myself a lot of confusion and tedious rewrites in the long run.

3) Compelling characters are those who are flawed.

During the course of my story, my protagonist created three imaginary friends, each of whom was some sort of fantasy creature with magical abilities of incredible power. Ironically, the only imperfection in each of these characters was the fact that they were perfect. They were all beautiful, intelligent, strong, courageous, and downright wonderful in every way conceivable. In retrospect, they were probably the personifications of the qualities I subconsciously wished or wanted to believe I had myself, with none of the drawbacks.

But there was a major problem with this: my characters were not relatable. Perfection was fine for my own daydreams, but nobody wants to read about impossibly powerful heroes who can save the day without so much as breaking a sweat (outside of comic books, that is). Readers want heroes who make mistakes, who fight for their goals with everything they’ve got and emerge triumphant after struggles that only made them stronger in the end. In other words, readers want to potentially see themselves in their heroes. And my characters didn’t fulfill that purpose. By designing them to be impossibly perfect, I had inadvertently made them every writer’s worst nightmare: boring.

4) Bad things must happen to good people.

Yes, I was one of those idealistic children raised on fairy tales, who believed that good always triumphed over evil, and the heroes should always defeat the villains in every battle, with no exceptions. This was reflected in the climax of my novel: when I finally introduced actual antagonists near the end of the story (another mistake, mind you), a series of fights ensued in which my main characters would always beat the bad guys every time they tried to attack. In the end, the villains were completely defeated, while the heroes were left without even a scratch. As you can imagine, that was a pretty boring scene.

This was probably the biggest flaw of my story: I had failed to create suspense. With every single attack of every single fight ending in the heroes’ favor, the scene that should have been the most exciting part of my novel became too predictable and bland. If, however, I had thrown a few twists into the mix, such as having one of my protagonists suffer a terrible injury that put her at the villains’ mercy, I could have set the scene up for a much more engaging and satisfying conclusion. In short, if anyone was going to care about whether my good guys would win the war, there had to be at least a chance that the bad guys might win a few battles first.

5) Your first book is going to stink… no matter what.

OK, maybe this isn’t true for all writers, but it’s likely true for most (if you’re one of the exceptions, I salute you). Sometimes I think that even if I had known everything else about planning and character development and conflict, my first novel still would have turned out mediocre at best. I was, after all, only ten years old; how well could I really have written a story reflecting important values of life if I had barely even started living mine? But even if I had started my first book in my twenties, I’m sure it still wouldn’t have amounted to a great classic of literature, because to know what to do in order to turn out a brilliant piece of fiction, I first would have had to know what not to do, and there’s only one truly effective way to learn that lesson…

I have absolutely no regrets about my first attempt at writing a novel. Although it was rather lame, I still love it for everything it’s taught me about fiction writing, and the fact that I was able to start gaining this experience at such a young age makes me all the more optimistic about my future as a writer. Today, I’m proud to say that I am once again working on a novel, this time with naturally flawed characters and a storyline filled with due drama and suspense, all planned out well in advance. From here on, there’s only room for improvement.

So what about you? If you’re a writer, have you been through a similar experience? What did you learn from your first mistakes in fiction writing?

by Naomi L. | May 22, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing |

No, I don’t actually believe in such a concept as “too much love”. If anything, the world could always use more love. But I’m not talking about world issues right now; I’m talking about romantic fiction.

Today’s topic is about the dangers of overusing the phrase “I love you” when writing romance. Now you might be wondering what exactly gives me the credibility to write about such a topic, and the answer is… not very much, except for my own amateur experience writing cheesy romance as a teenager and reading it again years later as an adult. So I’m just gonna talk about that.

When I was 16, I was a hopeless romantic. Now that I’m in my twenties… I’m still a hopeless romantic, but with a little more wisdom. As I’ve mentioned before, I spent part of my teen years writing medieval fantasy stories, among which was a star-crossed love story between a paladin (light-magic knight) and a necromancer (dark-magic sorceress). This story, so I had hoped, would someday develop into my first published novel. I was rather proud of it at the time I was working on it, even going as far as to share an excerpt of a particularly romantic chapter with friends. However, because my studies were highest on my list of priorities, the story was never finished, instead sitting in my computer as an incomplete novella collecting metaphorical dust over the course of a few years. It was after I started college that I finally rediscovered the piece among my archives, and after rereading my work with a fresh perspective, I finally began to take notice of some elements in the narrative that were – to my disappointment as a perfectionist but my delight as a neophyte at writing – dangerously clichéd.

When I was 16, I was a hopeless romantic. Now that I’m in my twenties… I’m still a hopeless romantic, but with a little more wisdom. As I’ve mentioned before, I spent part of my teen years writing medieval fantasy stories, among which was a star-crossed love story between a paladin (light-magic knight) and a necromancer (dark-magic sorceress). This story, so I had hoped, would someday develop into my first published novel. I was rather proud of it at the time I was working on it, even going as far as to share an excerpt of a particularly romantic chapter with friends. However, because my studies were highest on my list of priorities, the story was never finished, instead sitting in my computer as an incomplete novella collecting metaphorical dust over the course of a few years. It was after I started college that I finally rediscovered the piece among my archives, and after rereading my work with a fresh perspective, I finally began to take notice of some elements in the narrative that were – to my disappointment as a perfectionist but my delight as a neophyte at writing – dangerously clichéd.

Now, I won’t be going into excruciating detail about what made my unfinished story trite; I wouldn’t want to bore you with what could easily be thousands of words’ worth of self-criticism. Instead, I want to cover the main cliché in my work that jumped out at me the most: the aforementioned overuse of the phrase “I love you”. At the end of every romantic scene between the main characters, I would have them finish their conversation with those three words before they parted ways. It made sense to me that those should always be the last words they’d hear each other say until the next time they met. So what was wrong with that?

What I didn’t yet realize at the naïve age of 16 was that by having my characters actually say the words “I love you”, contrary to my intentions, I was creating less-than-believable dialogue. I was writing based on an instinct I’ve had my entire life: to always make sure these are among the last words I say to my loved ones before we leave each other’s company. Although this was perfectly normal for me (or perhaps because it was), it took me a while to realize that such a practice is not universally routine. Not everyone is accustomed to speaking the phrase several times in a single day; for many, it’s often just implied, if even that.

This, I realize now, is what I should have made clear with my characters. The love between them should have been implied, without the need for constant spoken confessions. By having them end every conversation with “I love you”, I was inadvertently detracting from the emotion that should have already been established outside of the dialogue: the way they looked at each other, the subtle gestures they exchanged, the littlest details of every kiss. This surely would have made their romantic moments much more believable, and more importantly, it likely would have made the moments that I did have them confess their love verbally all the more powerful. And isn’t that really the ultimate goal of writing romance in the first place?

Though I never did finish this particular love story, I don’t consider a single second spent writing it a waste of time. Leaving it untouched for a while helped me to see it again with the slightly wiser mindset of a young adult, and recognizing my own mistakes taught me about a part of my growth as a writer and a person that I might not have come to notice otherwise. But you don’t need to care about how this subject has affected me; what’s important for you to take away from this topic is a new awareness of how to recognize believable dialogue in romantic scenarios, especially if you plan on writing some yourself.

So if you appreciate romance as much as I do, please feel free to take my advice and learn from my mistakes (or even yours, if you’ve been through a similar experience). In short, writers should take care not to abuse the words “I love you”; if you wouldn’t do so yourself in your real life, you shouldn’t have your characters do so in your fictional works. “I love you” is a beautiful and magical phrase, but it can only remain so as long as it’s handled with the respect it deserves. Please write wisely; true romance enthusiasts everywhere thank you.

To help you avoid some common (and a few uncommon) grammar pitfalls, here are 25 examples of words and phrases you may be getting mixed up in your writing. Almost all of these items were taken from The Hodges Harbrace Handbook, an excellent resource for beginning and advanced writers alike. Be sure to check it out if you can! Write wisely!

To help you avoid some common (and a few uncommon) grammar pitfalls, here are 25 examples of words and phrases you may be getting mixed up in your writing. Almost all of these items were taken from The Hodges Harbrace Handbook, an excellent resource for beginning and advanced writers alike. Be sure to check it out if you can! Write wisely!

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the

When I was 16, I was a hopeless romantic. Now that I’m in my twenties… I’m still a hopeless romantic, but with a little more wisdom. As

When I was 16, I was a hopeless romantic. Now that I’m in my twenties… I’m still a hopeless romantic, but with a little more wisdom. As

Recent Comments