My Top Five Humor Tropes

What’s life without whimsy? Laughter truly is the best medicine, which is why many writers like to include a little comedy even in dramatic works. Humor is one of the most appealing genres of fiction, but it’s also one of the most challenging to write. That’s where humor tropes come in! When in need of a little comedy, a good humor trope may be just the thing to lighten the mood and keep your stories from becoming too grim.

So in the spirit of April Fools’ month, here are five of my favorite humor tropes. I hope you’ll find these as entertaining as I do! Enjoy!

1) Lampshade Hanging

Lampshade Hanging is easily my favorite humor trope. I wrote a whole post about it in my first few months of blogging! I just love when fictional characters draw attention to the ridiculousness of a situation they’re in, almost as if they’re purposely leaning on the fourth wall to let the audience know they “see it too”. The practice of “hanging lampshades” is a handy technique writers use to demonstrate their own awareness of intentional details in their stories that would otherwise be dismissed by the audience as mistakes or simply bad writing – a sort of “self-deprecation” device, if you will. Note that the best way to use a lampshade in comedy is as a standalone comment: bring it up once, then move on and never mention it again. A classic way to entertain your audience while keeping the critics at bay, Lampshade Hanging is a great go-to trope for adding a touch of clever humor to your stories!

Lampshade Hanging is easily my favorite humor trope. I wrote a whole post about it in my first few months of blogging! I just love when fictional characters draw attention to the ridiculousness of a situation they’re in, almost as if they’re purposely leaning on the fourth wall to let the audience know they “see it too”. The practice of “hanging lampshades” is a handy technique writers use to demonstrate their own awareness of intentional details in their stories that would otherwise be dismissed by the audience as mistakes or simply bad writing – a sort of “self-deprecation” device, if you will. Note that the best way to use a lampshade in comedy is as a standalone comment: bring it up once, then move on and never mention it again. A classic way to entertain your audience while keeping the critics at bay, Lampshade Hanging is a great go-to trope for adding a touch of clever humor to your stories!

2) Brick Joke

It’s gonna be legen… wait for it… [falls asleep]

You know when a joke is set up at one point in a story only for the punchline to come later, when you’ve almost forgotten about it? Well, that’s a special kind of humor device called a Brick Joke. This is the comedic version of the Chekhov’s Gun, when the conclusion to a funny scene is delivered separately from its beginning after several unrelated events have happened in between. This trope is named after an old joke consisting of two parts, the first ending with an underwhelming punchline about a brick and the second ending with a twist that recalls the same brick. The humor of a Brick Joke comes from subverting the audience’s expectations: what at first appear to be separate situations turn out to be two parts of the same joke. To properly execute a Brick Joke, scatter a few jokes between the set-up and the punchline so as to either dissuade the audience’s suspicion that the first part was building up to a joke or trick them into thinking the first part was the joke. With the right timing, this trope can score major laughs from your readers! They won’t know what hit ’em!

[5 minutes later; waking up when the door slams] -dary!

– Barney Stinson, How I Met Your Mother (Season 2, Episode 11 – How Lily Stole Christmas)

3) Running Gag

Ooooh! (Puss in Boots, 2011)

A sister trope of the Brick Joke, the Running Gag is another popular comedic device, especially in TV series. It’s also one of the riskiest; when done poorly, it quickly becomes annoying, but when done well, it can rake in a lot of laughs. A Running Gag is basically a joke that’s repeated over the course of a story or series (a minimum of three times), sort of like a recurring punchline to the same Brick Joke. It usually involves the same character(s) each time it comes up, though this needn’t be the case when the humor of the gag is entirely in the action itself. The key to a good Running Gag is timing: space the punchline recurrences far enough apart to keep the joke from wearing out too quickly, but add enough recurrences to draw as much laughter from the audience as possible. This may take a lot of practice to get right, especially since humor is so subjective, but once you get the hang of it, the Running Gag can make an excellent addition to your arsenal of comedy tropes!

4) I Resemble That Remark

Amy: You were being totally obstinate!

Knuckles: I don’t know what “obstinate” means, but I refuse to learn.

– Sonic Boom (Season 1, Episode 22 – The Curse of Buddy Buddy Temple)

Sometimes in comedy, one character will call another out on a flaw, only for this second character to object… in a way that demonstrates the exact flaw they’re denying. I Resemble That Remark is one example of the many humorous uses of irony, in this case comically subverting characters’ perceptions of themselves. It’s one of those comedic devices that draws its humor from an element of truth, as it plays on the all-too-common scenario where a trait that a person will swear is nothing like them will in fact turn out to be one of their defining characteristics. Think of it as an exercise in learning to laugh at yourself; if you find yourself identifying with fictional characters who can’t see their own shortcomings, maybe it’s time to reevaluate that idealized self-image!

Monica: Rachel always cries!

Rachel: [sobbing] That’s not true!

– Friends (Season 4, Episode 4 – The One With The Ballroom Dancing)

(Source: Tumblr)

5) Hypocritical Humor

Mike: I’m gonna go to the bathroom.

Phoebe: Okay, well you put down the toilet seat.

Mike: Yes, dear. [leaves]

Monica: Is that a bit you guys do?

Phoebe: Uh-huh, we’re playing you two.

Monica: We don’t do that! [to Chandler] Tell her we don’t do that!

Chandler: Yes, dear.

– Friends (Season 9, Episode 16 – The One With The Boob Job)

The previous item on this list is a subtrope of a device known as Hypocritical Humor. This trope comes in a variety of flavors: saying one thing and doing the exact opposite, exhibiting a behavioral flaw immediately after denying said behavior, criticizing or making fun of others for faults of which the accuser him- or herself is guilty, or ignoring several warnings of an impending event only to get upset when said event happens. One particularly hilarious form of this trope is when the irony comes from the universe aligning itself exactly right to contradict a statement the exact moment after someone says it, which can either be a way of tempting fate or invoking karmic justice, depending on the nature of the statement. Note that Hypocritical Humor in fiction constitutes jokes that are intentionally added to a story to be played for laughs; unintentional hypocrisy is more likely attributable to bad writing and, in cases where it still evokes some laughter, may fall under a phenomenon known as Narm (that is, what is meant to be serious but is accidentally funny instead). Be careful how you deploy that hypocrisy in your fiction!

What are your favorite humor tropes? Which humor tropes have you used in your stories?

My Top Five Romance Tropes

It’s almost Valentine’s Day, and that means it’s the best time of year to indulge in some romance! To mark the occasion, I went through some of the romantic tropes on TV Tropes and put together a list of my favorites. So to help inspire your romantic creativity for Valentine’s Day, here’s a list of my top five romance tropes. Enjoy!

1) The Power of Love

Belle and Prince Adam (Beauty and the Beast, 1991)

Of all the romantic tropes I’ve ever seen in fiction, The Power of Love is by far my favorite. It’s the main reason romance has always been one of my favorite genres. I have a weakness for stories in which love triumphs over hate and helps characters grow and change for the better. Call me a hopeless romantic, but I honestly believe that love can indeed conquer all. This one doesn’t even have to be a romantic trope, as love comes in many forms, none of which are necessarily the strongest or most influential of all. Whether it’s the healing magic of True Love’s Kiss or the driving force behind a mother and father‘s protection of their children, The Power of Love can change the world!

2) Love at First Sight

I admit it’s ironic that this trope is on my list given that I’m not sure I completely believe it can happen in real life, but I absolutely love reading about true love at first sight in fiction, especially when it works out in the end. There’s just something so uplifting about the idea of two people instantly connecting on a spiritual level and knowing beyond a shadow of a doubt that they’re meant to be together. Love at First Sight can go either way: the couple may really be perfect for each other and eventually earn a Happily Ever After, or they may simply be sharing a passion that’s doomed to burn out (in which case it’s really more of an infatuation at first sight).

Ted and Robin – How I Met Your Mother (Season 1, Episode 1 – Pilot)

Of course, if the two lovers are a good match but the story calls for them to be kept apart anyway, this can become a tale of…

3) Star-Crossed Lovers

Romeo and Juliet (Romeo x Juliet, 2007)

Admit it, you knew this was coming: another chance for me to gush about Romeo & Juliet! The most famous Star-Crossed Lovers in literature (and the trope namers), the young protagonists of my favorite romantic story shared a passionate and dangerous love affair that was doomed to a tragic end. Though a strong case can be made that Romeo and Juliet were indeed soulmates, the sad truth is that their love was not strong enough to overpower fate. Of course, it’s still fair to say that their love did triumph over hatred in the end: by taking their own lives to be together eternally, they finally ended the feud between their families.

The tale of Star-Crossed Lovers is one of the greatest literary devices that can demonstrate the powerful contrasts between love and hate, and that’s probably what makes it one of the most enduring plot structures in the history of romantic fiction. It seems no matter how many times this tragic story is retold, Romeo & Juliet never gets old!

4) Childhood Friend Romance

Simba and Nala (The Lion King, 1994)

On the other side of the love spectrum, we can also see two people who have known each other their whole lives but who only develop feelings for each other in maturity. Some of my favorite love stories involve a Childhood Friend Romance, a story about characters who’s affection for one another started at a young age and eventually became the foundation for a solid loving relationship (my favorite example is the seven-book buildup to the relationship between Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley).

It doesn’t have to be a romance that began in childhood, of course; my parents, who met in their young adult years, are a perfect example of how any relationship that started as friendship can blossom into everlasting love. Still, there’s something about a story of two lovers who were meant to be together since childhood that warms my heart every time. Can you say “D’awww”?

5) Babies Ever After

Harry Potter and his son, Albus Severus Potter (Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, 2011)

Whether two characters fell in love at first sight or grew to love each other over time, a happy ending is a happy ending, and my favorite kind of happy ending is one that keeps on going. I don’t know about you, but I’m not always satisfied with just “and they lived happily ever after, The End”; I want to see what happens next! That’s why I love a good epilogue, especially one that shows the main characters in the future with children of their own!

I’ve made it only too clear in the past how much I love the Babies Ever After trope: the most popular story I’ve ever written is a second-generation fanfiction set in the universe of my favorite video game characters. The idea of the canon characters having families in the future was so fascinating to me that I just couldn’t resist writing my own story about it! Not that I have anything against the choice not to have children; I just happen to have a soft spot for family love and next-generation characters. May the stories live on!

What about you? What are your favorite romantic tropes?

Hitchcock’s Icebox: Fun with Fridge Logic

You know when you’ve finished watching a movie/TV show or reading a novel, only to suddenly realize hours later that there was something odd about the plot? Well, what you experienced was a trope known as Fridge Logic, that peculiarity in a story that only hits you in a moment of idle thinking. It’s an interesting concept with which I’m becoming increasingly familiar, so today’s creative writing post briefly covers what it is and what it means for fiction writers. Enjoy!

Why a fridge?

Huh, empty. Like the hotel room in that– Wait a minute…

No, this trope doesn’t necessarily have to do with an actual refrigerator. According to TV Tropes, the term “fridge logic” can technically be traced back to Alfred Hitchcock, who once referred to a particular scene in his film Vertigo as an “icebox scene”. In the words of the director, it’s the kind of scene that “hits you after you’ve gone home and start pulling cold chicken out of the icebox”. Basically, Fridge Logic refers to a special kind of plot hole that you don’t notice at first because you were so caught up in the story that you didn’t bother to think about consistency at the time.

So what does this mean for you as a writer? It means that no matter how well you try to get away with a plot hole in your work, anyone anywhere at any time is bound to find it. Of course, how much that really matters is a subject for another time.

The Other Sides of Fridge Logic

That moment of clarity that hits you at the fridge doesn’t always have to be a bad thing. Sometimes what you realize is the cleverness embedded in a certain story element. This is known as Fridge Brilliance. It usually refers to a part of a story that you didn’t care for at first, only to come to appreciate it after you’ve finally recognized the true meaning behind it. And that, in my opinion, is pretty darn cool.

Another form of Fridge Logic covers the other side of the spectrum, when something you didn’t really notice at first becomes terrifying in hindsight. This is referred to as Fridge Horror. As noted on its TV Tropes page, there are two kinds of Fridge Horror: the horrifying story elements that went over our heads as kids but that have become blatantly obvious to us as adults (Frozen-By-Time), and those that reveal themselves after we take the time to really think about their implications beyond the immediate story (Quickthaw). Look for these at your own risk: remember, anything awful you see in a beloved work of fiction cannot be unseen!

Fridge Logic has the obvious risk of slightly taking away from an otherwise good story, but you can’t deny that it can be tons of fun to discuss once you’ve experienced it. Plot holes should usually be avoided altogether, but if you absolutely must include some, try to hide them well enough that they only become clear in hindsight. At least then you’ll be giving your readers something extra to discuss after your story is over! Good luck!

Have you ever experienced Fridge Logic before? What sorts of plot holes have you found in your favorite works of fiction?

Follow That Fish: How to Drop Red Herrings in Your Stories

Some time ago, I wrote a blog post about a trope known as Chekhov’s Gun, a literary device in which a seemingly unimportant detail later becomes significant to the plot. But what if you want to achieve the opposite effect, that is, introduce a supposedly important detail that later turns out to have little or nothing to do with the main story? Today’s post features a sister trope that’s equally useful and just as fun to write. Do you enjoy misleading your readers with deceptive clues? Then let me introduce you to the next handy tool in your arsenal: the Red Herring.

Herring? Where?

The “red herring” is a type of heavily cured/smoked kipper. The idiom may have originated from anecdotes relating its use as a tool for misleading hunting dogs.

(CC Image by misocrazy via Flickr)

The Red Herring is a common device in fiction, employed by writers who like to keep readers on their toes. Simply put, it’s a clue intended to lead in the wrong direction. This is an especially useful trope for plots that involve a lot of mystery, as misleading details help to keep the element of surprise. After all, a story in which the major secret is easy to deduce from the beginning isn’t really worth the read, is it?

Like the Chekhov’s Gun, a Red Herring generally relies on the principle of conservation of detail to work properly: every detail presented in a story must have a reason for being there, otherwise it should be discarded. Of course, as mentioned above, a Red Herring functions in the opposite manner as a Chekhov’s Gun in that it’s intended to seem important upon its introduction but is later revealed to have been a distraction from the true secret of the story. The challenge for the audience is trying to tell the fake clues from the real ones!

Placing a Red Herring

Although every Red Herring is purposely used to throw the audience off, the best ones still have some significant connection to the plot even after being revealed as false leads. For instance, a clue can be introduced to set up suspicions about a certain character. This character may later turn out to be innocent, but the clue that seemed to be pointing to them justifies another character as the culprit instead. The example provided on TV Tropes is that of suspects in a hypothetical murder case, but I suppose it could apply to any kind of mystery. The only limit is your own imagination!

For writers who like to get really creative, Red Herrings come in different “flavors”. Subtropes include the Red Herring Shirt, when someone in the background turns out to be an important character; the Red Herring Mole, when a character who seems suspicious turns out to be innocent; and the Red Herring Twist, when a detail played as a potential Chekhov’s Gun turns out to be nothing more than a distraction from the main plot. It’s also possible to create a similar effect with a mistake as opposed to intentional misdirection, while a plot twist confused for a Red Herring due to its overly obvious nature is known as an Untwist.

Overall, I find Red Herrings very enjoyable to write, for when placed well, they can definitely add some interesting twists to a story. Have fun trying them out for yourself, and good luck throwing your readers off with misleading clues!

Love at First Sight: Fantasy or Non-Fiction?

Ah, love at first sight. It’s a beautiful idea, and with Valentine’s Day fast approaching, it’s easy to get lost in such a romantic thought. This is a trope that’s been present in romance for centuries. Romeo and Juliet, Cinderella and Prince Charming, Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere; all are well-known examples of couples in fictional tales and legends who fell in love instantly. But is love at first sight just a myth fit for fantasy, or is it real enough to warrant a place in more naturalistic fiction?

What is Love?

What a complex yet simple question. If you were to ask several different people what love is, you’d probably get several different responses in return. Everyone seems to have their own explanation, and the most interesting part is that they aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive.

Socially, it’s a strong positive connection between two people. Psychologically, it’s a form of deep affection for another being. Biologically, it’s a chemical reaction in the body that creates a feeling of intense passion. There are many ways to characterize love; it all depends on your chosen perspective and your personal experiences with it.

So what about love at first sight? If love is clearly possible between two people, can such a powerful attraction happen instantly?

The Science of Love at First Sight

Romeo and Juliet fell in love the moment they first laid eyes on each other (Romeo + Juliet, 1996)

I asked a few people I know for their thoughts on love at first sight, and to my surprise, the answers I got came from both sides of the debate. On the one hand, my mom (as well as most other people I asked) believes that such a concept is impossible in real life because love is based on something more than physical attraction, something you can’t discover until you’ve really gotten to know the other person. On the other hand, my dad not only believes in love at first sight, but he swears it’s happened to him at least once in his life. To hear others tell it, it was mostly likely infatuation at first sight, but if he believes it was love, who are we to say otherwise?

Oddly enough, some studies seem to suggest that love at first sight is indeed possible. I’ve read some interesting takes on the subject on sites like HowStuffWorks, Psychologies and Daily Mail, to name a few. Of course, it’s worth noting that most arguments defending the concept refer foremost to the physical side of love, but then again, what are human beings if not mostly flesh and blood, right? What matters is that science seems to support the idea that two people can accurately size each other up within the first three minutes of meeting, and have a good chance at making a subsequent relationship work.

Fiction or Reality?

So what does all this mean to writers of romance? I suppose it means whatever you want it to. Characters in fantasy stories can certainly fall in love instantly without compromising the plausibility of the plot; at the very least, the attraction could be attributed to magic. Yet writers of realistic fiction could also possibly make their characters fall in love immediately and get away with it, provided the event is narrated well enough to work in the context of the story.

As for me, even though I’ve never really experienced it myself (unless you count my first crush in Kindergarten), I like to believe that anything is possible. I don’t normally write about it in my own stories, as I prefer to have my characters’ relationships develop over time, but I wouldn’t discard the idea for a future project. It might be fun to explore the possibilities that come with falling in love at first sight!

What about you? Do you believe in love at first sight? Would you impose such a fate on your characters?

The Secret Plot Device: Chekhov’s Gun and How to Fire It

*click*

Have you ever read a story or watched a movie/play where you noticed a certain item being used as an important plot device in a major scene, only to realize that the object in question had already made an appearance in a previous scene as some seemingly insignificant prop in the background?

Well, what you witnessed was the figurative (or in some cases, literal) firing of a Chekhov’s Gun.

The Loaded Rifle on the Wall

The Chekhov’s Gun is a literary technique that places significance on a certain story element that was introduced earlier on as an unimportant detail. The trope is based on a dramatic principle conceived by Russian playwright Anton Chekhov (1860-1904), which states that every detail presented in a story must either be necessary to the plot in some way or removed from the narrative altogether.

If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.

– Anton Chekhov (S. Shchukin, Memoirs. 1911)

Of course, sometimes it’s not just a metaphor…

(CC Image by tmib_seattle via Flickr)

It’s important to note here that a Chekhov’s Gun is not necessarily an actual gun; the playwright’s example was merely used in reference to live theater, where a loaded gun on stage would pose an unnecessary safety hazard if it wasn’t going to be used as anything more than a background prop. Rather, the device is a metaphor for any element of a story that can become important later on. It doesn’t even have to be an object; it can just as easily be a character, a skill, a line of dialogue, etc. A full list of possibilities and variants can be found at the TV Tropes Chekhov’s Gun Depot.

Handling a Chekhov’s Gun in Your Writing

There are two main concepts connected with this trope:

- Conservation of Detail – Every detail presented in a story has an important reason for being there

- Foreshadowing – A detail given early on is an indication of a plot point that will happen later in the narrative

While a Chekhov’s Gun should really be used with the former concept in mind, it’s most commonly associated with the latter. Writers will often use this trope as a tool to indicate upcoming events in the story, usually in a subtle manner that goes virtually unnoticed the first time around and becomes clear after the revelation of the foreshadowed plot point.

So how should you use this technique in your own stories? To properly execute a Chekhov’s Gun, the element in question must have some level of presence established in its introduction, not necessarily so much that it gives away a potential plot twist, but enough that the audience will realize it was there all along by the time it becomes significant. This will keep your readers from assuming you pulled some random solution out of thin air to hastily tie the plot together at the end, and thus prevent you from evoking their disappointment.

Also, bear in mind that there is such a thing as too many Chekhov’s Guns in one story. While you shouldn’t feel limited to just one per narrative (and many writers aren’t, myself included), you should still take care not to go overboard with the trope. Of course, these limits may vary depending on the type of work in which it’s used; for example, fantasy sagas or mystery thrillers may depend heavily on these devices to help drive the plot (as seen in the Harry Potter series, which even has its own Chekhov’s Gun page on TV Tropes), whereas simpler action stories could work just fine with only a couple at most. So if you’re planning to write long narratives full of twists, you might be able to make good use of this technique throughout the entire story arc. It’s worth noting, though, that if the plot becomes convoluted enough, your readers might eventually start looking for significance in the tiniest details to try to find Chekhov’s Guns that you may or may not have placed in your story. But then again, maybe that’s exactly what you want.

The Chekhov’s Gun can be a useful device in fiction, provided it’s used correctly and in proper tone with the story. Whether you choose to use this technique for major plot points or just to add some interesting twists, be sure to always keep in mind the importance of only including details with a given purpose, and you’ll be able to build a narrative that highlights the plot and tells a story that can be freely complex on the surface while remaining simple and straightforward at its core. And that, in my opinion, is the best type of story a writer can create. Happy writing!

*BANG!*

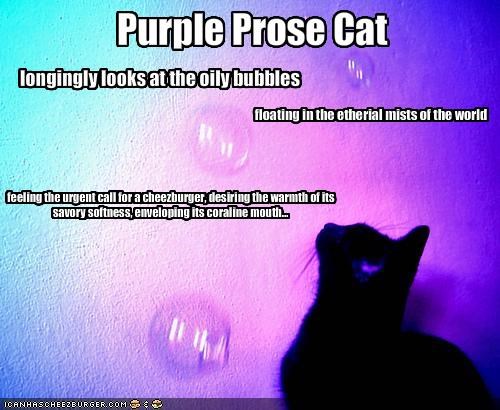

Composition of the Amethystine Variety and Why One Must Abstain From Its Application (or “Purple Prose and Why You Should Avoid It”)

I’m polymerized tree sap and you’re an inorganic adhesive, so whatever verbal projectile you launch in my direction is reflected off of me, returns on its original trajectory, and adheres to you.

– Dr. Sheldon Cooper, The Big Bang Theory (Season 1, Episode 13 – The Bat Jar Conjecture)

Fans of the comedy TV series The Big Bang Theory likely remember this quote from the Physics Bowl episode, when Sheldon reacts to an insult from fellow physicist Leslie Winkle by saying as condescendingly as possible that “he is rubber and she is glue”. However, the fact that he seems to go out of his way to use the most advanced vocabulary possible in his retort only adds to the hilarious running gag of Leslie always managing to beat her rival at a game of wits.

So what lesson should novice writers be learning from Sheldon’s backfired comment? That trying too hard to sound smart often has the opposite effect than what you might expect, that is, it hurts more than it helps.

What is this amethystine composition of which you speak?

Writing that is overly decorated with fancy words and elaborate details is known as “purple prose”. It’s an especially common practice among inexperienced writers, who often believe that to write a really good story (or improve upon an existing dull one), one needs to dress up the prose with as many big words as possible to make their work look sophisticated. Basically, beginners seem to have this grand illusion that great literature is that which stands above the level of everyday speech.

Purple prose: Contemplate this exquisite aubergine blossom of the Rosaceae family

Everyday speech: Look at this beautiful purple rose

But here’s the problem with that logic: everyday speech is the level where most readers are, and more importantly, where they want to stay. Readers today don’t want to bore their way through long descriptions or have to pause at every other page to look up half the words they just read in the dictionary. They want writing that’s simple, that they can understand and find relatable, similar to the language they use themselves in the real world.

So I’ve been writing erroneously… I mean, wrong all this time?

Calm down, and take a second to note that I said “similar to”, not “the same as”. It’s OK to use some higher-level vocabulary and detailed narration in your stories, for when done in moderation and in tone with the style of the work, these can actually add to the quality of your writing. The danger is using these tools in excess, because after you’ve passed a certain point in flowering up your prose, these details will begin to draw attention to themselves and away from the flow of your story. To sum up, a little is fine, but too much is bad. Write with caution.

Now before anyone accuses me of hypocrisy, allow me the chance to admit to this embarrassing fact: I am guilty of writing purple prose. Even if I don’t always choose the fanciest synonyms I can find to replace everyday words, I love decorating my writing with adjectives and adverbs, and I tend to use intermediate-level words where common ones would work just fine. That being said, I used to be much worse. When I first started writing, I had this idea that nobody would want to read stories written in the plain language of a ten-year-old, so even though I was already well-read for my age, I went out of my way to find “bigger and better” words for my fiction. It wasn’t until I started learning about common writing mistakes as a young adult that I realized how flowery my early writing was, and I’ve since been gradually cutting the bad habits of my childhood. So take it from a writer who’s still breaking out of the novice phase: tone down the purple and focus on writing simple prose. Your readers will appreciate it.

It’s worth noting at this point that as strongly as most experienced writers will argue against this practice, prose style is and always will be subjective. It’s entirely possible for a writer to not only be aware they write such elaborate prose, but actually do it on purpose. So if you’re a beginning writer guilty of this trope, don’t feel bad right off the bat. Maybe your goal is to imitate the exact styles of writers like William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens and Jane Austen, and that’s fine. Just know that unless you’re going for satire, most of the audience who would take your work seriously has probably been dead for a few hundred years.

It’s worth noting at this point that as strongly as most experienced writers will argue against this practice, prose style is and always will be subjective. It’s entirely possible for a writer to not only be aware they write such elaborate prose, but actually do it on purpose. So if you’re a beginning writer guilty of this trope, don’t feel bad right off the bat. Maybe your goal is to imitate the exact styles of writers like William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens and Jane Austen, and that’s fine. Just know that unless you’re going for satire, most of the audience who would take your work seriously has probably been dead for a few hundred years.

But I want to be taken seriously today! What should I do?

Don’t worry, the “purple prose bug” is treatable! For those of you aspiring writers who wish to establish yourselves before you try to follow the great authors who bend the rules, here’s a quick list of common purple prose mistakes and how you can avoid them:

1) Excessive detail. Yes, describing the setting of a scene before the action starts is often essential to telling a good story, but please don’t go on for a dozen pages about the hundred different colors in the sky or the history hidden in every brick of every building. Just because authors like J.R.R. Tolkien and Victor Hugo could get away with it doesn’t mean you can. One paragraph should be enough to set your scene, but no more than two.

2) Overly decorated nouns and verbs. If you’re one of the millions of readers who have read all of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books, you may have learned that nouns and verbs should almost always include a “modifying friend”. But Rowling is an exception, a world-famous author of one of the best-selling book series in history, which you are (probably) not. That means she can do whatever she wants with her writing, whereas you should practice creating basic prose before you work too hard to copy her style. Try not to use too many adjectives and adverbs in your writing. Though this may seem counterintuitive, many famous writers would agree that less is more. If you don’t believe so, read a story by Ernest Hemingway or Mark Twain, and you’ll see how writing can be great without the need for too many “attachments”. To quote Twain, “When you catch an adjective, kill it.”

3) Said bookisms. This is one of the most common mistakes made by beginning writers: the constant use of alternative verbs for the word “said”. There’s a general belief that when it comes to writing dialogue, “said” is too plain and overused, so writers should go out of their way to replace it with words like “asked”, “muttered”, “hissed”, etc. As a teenager, I used a lot of these in my writing; I wouldn’t be surprised if I read back a dialogue-heavy scene from one of my old stories and found at least three pages between consecutive uses of “said”. But even famous authors seem to be guilty of this sometimes (I’m given to understand there’s an entire blog devoted to poking fun at the purpleness of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series), so don’t feel too bad if you find your own writing full of these bookisms. The important thing is that you know you should fix them. Dialogue should convey tone by itself, no extra tags required.

4) Too much “fancy vocabulary”. Continuing from the example of “said”, some writers tend to try and find as many advanced-sounding synonyms as possible to substitute the common words in their stories. While this may be fine once in a while, you shouldn’t run to the thesaurus for every other word you want to write. Otherwise, you’ll end up sending your readers to the dictionary just as frequently. It’s great to learn new words, but think about it for a second: the more time you put into driving your audience to read another book, the less time they’ll spend reading yours. Try to stick to vocabulary that your readers will understand, and if you must throw in a higher-level word now and then, at least have the courtesy to make its definition clear in context.

5) Exaggerated sentiment. There isn’t a lot I can say here except that this is pretty much a writer’s attempt to manipulate the reader into reacting a certain way to their writing. Going back to the first item on the list, if you throw too much rhetorical writing into your stories, it comes across as you trying too hard to evoke specific emotions from your readers, which more often than not will have the opposite effect. Trust your audience to understand what you’re trying to tell them. If you write it plainly enough, they will feel it.

Purple prose is a dangerous habit of many writers, and while it may be OK for some, most should make a point of avoiding or overcoming it, no matter how difficult this seems. If nothing else, choosing to create simple and clean prose is a sign of respect to your work and your readers, so take care with your style of writing. I’m certainly still trying.

So what are your experiences with purple prose? Have you read stories that you found too flowery for your taste? Were you (or are you) ever guilty of making these mistakes yourself?

An Attempt at a Clever Title: The Topic of the Blog Post

Confused about the title? Or maybe you’re confused about my asking if you’re confused about the title? Or maybe you’re confused about my asking if you’re confused about my asking if you’re confused about the title? Or maybe you’ve had enough if this nonsense and just want me to get to the point?

This week’s creative writing topic is an interesting trope of which I’ve become rather fond over the course of my own writing: a technique known as “lampshade hanging“, or simply “lampshading”. It’s an idea I first learned about when reading TV Tropes, and because of the way I often see it being employed in humorous writing, it’s quickly becoming one of my favorite devices in fiction. But you probably don’t care yet what I think about it; you’re just waiting for me to explain what it is so you can decide whether you’d like it too. Unless you went ahead and skipped to the next paragraph before reading this one and already realize how I’ve been incorporating the trope into this blog post. Am I right?

This is not the lamp you’re looking for…

OK, no more stalling. Lampshade hanging is a trick employed by writers to address any noticeable implausibility or obvious trope usage in a plot by drawing attention to it… and then moving on. But wait, why would you want to point out your story’s flaws in the first place? Counter-intuitive as it may seem, this exercise does have a few advantages:

- It proves you aren’t trying to get away with a questionable plot development by showing your audience that you’re also aware of the absurdity;

- It establishes a sense of realism in your story by demonstrating that your characters are just as skeptical about the implausibilities in the plot as the real-life people following it; and

- It’s a way to beat critics to the punch of deprecating you for the “mistakes” you already know are in your story.

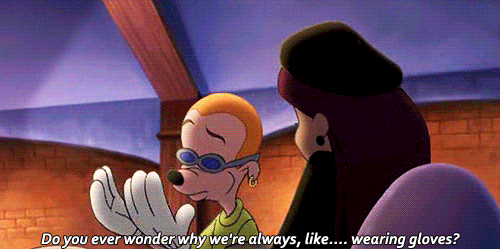

Need an example? Here’s a rather brilliant one from my favorite moment in the 2000 Disney film An Extremely Goofy Movie, when Bobby Zimmeruski randomly realizes something strange about the world around him…

You know you’ve always wondered the same thing…

The best part? This question is almost immediately dismissed and never comes up again for the rest of the movie!

It should be noted that whenever a writer “hangs a lampshade” on a particularly glaring plot hole, it could be taken as a hint from their subconscious about the true extent of an unforgivable absurdity in an otherwise serious work. Of course, the technique can also be observed in use to the extreme in stories that are intended to be especially humorous and even self-aware, which (when done well) can be very entertaining (like in this product placement clip from the comedy TV series 30 Rock, which brilliantly demonstrates Tina Fey’s mastery of humor tropes). Mostly, though, it works just fine when used in moderation, kind of like a brief comic relief to complement the action in the rest of the story.

Bonus note: aside from “lampshades”, the practice is also known as hanging a “red flag”, “lantern”, or “clock”. The trope is referred to as “lampshade hanging” in my blog because it’s the most common term used on the TV Tropes website, which in turn attributes the phrase to Mutant Enemy.

While I don’t hang lampshades often in my fictional works, I do enjoy throwing them into my blog posts now and then, which I tend to use for humorous purposes as a personal reminder not to take myself or my writing too seriously (a flaw of which I’m painfully guilty, possibly evidenced by the fact that I don’t like to end phrases with prepositions). Hopefully my readers find them entertaining, or at the very least, tolerable. I do enjoy practicing lampshade hanging, and if you like to keep an element of comedy in your own writing, you might like to take it up too!

Now if you’ll excuse me, I must go do extensive research for the next blog topic on which my novice writer’s knowledge is still relatively limited. Thanks for reading!

TV Tropes, a.k.a. The Greatest Website That Will Ruin Your Life

Do you ever find yourself reading a book or watching a movie and noticing certain elements in the story that you’re sure you’ve seen before in the plots of other works of fiction? Or better still, do you ever find yourself talking about stories from these media and mentioning said elements in the form of a question that starts with, “You know that thing where…”?

Chances are there’s a trope for that.

What is a trope, you ask? Well, it’s not entirely easy to explain, as the definitions may vary slightly based on opinion. The simple definition is that tropes in fiction are devices that have become common enough throughout their respective media to have established themselves as conventions in the minds of the audience, and thus are reliable to writers as useful tools in creating fiction. A slightly more complex definition expands on this simpler one to also include examples of such conventions in real life, as in behind the scenes or even real-world events. Of course, a much more thorough explanation can be found on the website’s homepage itself, so instead of launching into a long and tedious description of TV Tropes and its endless supply of examples, I’ll simply provide a brief account of my own experience with the site and leave the option of following the link provided to your own discretion.

One of my first visits to this site was when I was looking up information about a certain Disney movie (I want to say it was Tangled, but my memory fails me). What I found was an abundance of tropes used throughout the film that could be easily recognized as conventions present in the plots of other stories (Character Development, Non-Human Sidekick, Happily Ever After, etc.). I was so intrigued by this new resource I had discovered that it wasn’t long before I started referring to it for examples of tropes in other fiction works – films, TV series, literature – learning more about these devices with each page I opened.

So why would I say this site will ruin your life? Because there’s a very good chance that at least once (and probably on your first visit), you’ll fall into the same trap I did: the web of tropes. On virtually every TV Tropes page, there will be a link that catches your eye, leading you to another page with more interesting information and new links, which in turn lead you to other pages with their own intriguing links… until the next thing you know, it’s an hour later and you can’t remember which page you originally meant to read without checking your browser tabs or history for a reminder. How did that happen?

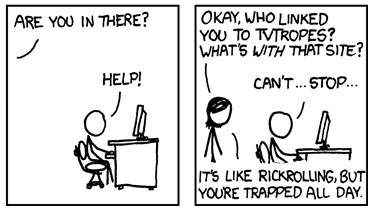

In case you need a visual aid, my experience with TV Tropes (and that of countless others) can be summed up in this webcomic. (Courtesy of xkcd)

Here’s an example of one of my typical TV Tropes sessions: I start by opening the page of a classic Disney film, let’s say Beauty and the Beast. One of the listed tropes is the famous True Love’s Kiss, complete with a brief explanation of how the instance in this particular movie is more of a variation than a straight example, which sparks my curiosity to read about other examples in different works. A moment later, I’m reading this trope’s description on its own page when… Wait, what in the world is a Dead Unicorn Trope? Obviously I go to that page to find out, only to realize in two seconds that I’ll first need to know what a Dead Horse Trope is in order to understand the unicorn variation, but this one interestingly turns out to be a common cause of a phenomenon known as Seinfeld is Unfunny… Several pot holes later, I’m back at the True Love’s Kiss page reading about how it’s a subcategory of a greater trope known as the Magic Kiss, leading me into another chain of links through the site. After another half hour, I go back to reading the list of tropes in Beauty and the Beast, where I soon find another trope that intrigues me, and the whole thing starts all over again.

But you know what? I love every minute of it, because even if I know TV Tropes will ruin my life on one hand, in a way, it also enhances my life on the other.

Now that’s what I call Troperiffic!

(Image by AgentCoop of Cracked.com)

TV Tropes is an excellent resource for anyone who appreciates works of fiction, and especially for writers of such works. Learning about the various devices used in media and how they function in their respective plots teaches us how to analyze fiction critically, allowing us to develop a keener understanding of the elements that make up a story. This is particularly important for writers, because we more than anyone else should have as thorough a knowledge as possible in the workings of the stories we wish to create. How can we expect to write good fiction if we don’t have a decent understanding of the myriad of tools at our disposal?

So yes, by pulling you into its vortex of interesting content, TV Tropes may easily ruin your life. But in the end, if you somehow emerge with a refined outlook and even a new respect for the fiction you already love, then wouldn’t you really just be exchanging it for a better life?

Recent Comments