by Naomi L. | October 23, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Featured |

Remember the elementary school days when our teachers introduced us to those trusty reference books that would guide us through our writing? These were the friends we would come to rely on for the rest of our lives, the books containing so many of the answers we would need to survive our school years. The dictionary told us what those long words we’d never seen before meant. The atlas helped us find those faraway places we’d heard about in Geography class. There were encyclopedias and almanacs full of facts that came in handy for homework assignments. And then there was that book that gave us lists of synonyms and antonyms for the words we wanted to use in our writing: the thesaurus.

This last book is an interesting case, though, because unlike the others, it has the same potential to hinder as it does to help. Yes, the thesaurus is a top go-to resource for many writers, especially beginners looking to enhance their work. However, something our teachers may have neglected to tell us is that the guide comes with unwritten instructions: use knowledgeably.

Trustworthy/reliable friend/ally?

“Hooray yay for synonyms!”

(Screenshot from RubberNinja‘s Gameoverse videos)

When we were first introduced to the thesaurus, we were taught that it’s a great resource for helping to expand our vocabulary, and that’s true. I can’t even count how many new words I’ve learned just by looking up synonyms for ones I already knew. Every time I work on my stories, I have my dictionary/thesaurus widget handy to help me find replacements for words that would otherwise be repeated too soon in the narrative. It even helps me remember advanced vocabulary that I may have forgotten (which happens more often than I’d normally care to admit).

A good use of a thesaurus is as a reverse dictionary. You know how sometimes you know exactly what you mean to say, but you just can’t find the right word for it? Well, all you have to do is look up more common words for the definition you want and see what options come up. True, this method may not be as effective as using an actual reverse dictionary, which has full definitions and cross referencing, but it’s still a convenient alternative to find simpler examples, especially for writers who don’t have access to a more complete guide.

So yes, writers, the thesaurus is your friend. It will save you from plain and repetitive writing, and can teach you a thing or two (or ten) in the vocabulary department. But be warned, because placing too much trust in this guide can have negative consequences as well…

Or dubious/suspicious enemy/foe?

So how could this dependable friend of ours also be a hazard to our writing? Instead of launching into a dissertation about the dangers of overusing a thesaurus, allow me to illustrate the point instead with an example from the popular TV series Friends. In this episode, Joey wants to write a letter of recommendation for Monica and Chandler, who are planning to adopt. When he mentions that he wants to make it sound smart, Ross suggests he use a thesaurus to replace plain words with advanced ones. Unfortunately, the results are less than satisfactory…

Joey: Hey, finished my recommendation. (hands a letter to Chandler and Monica) Here. And I think you’ll be very, very happy.

[…]

Chandler: I don’t, uh, understand.

Joey: Some of the words a little too sophisticated for ya?

Monica: It doesn’t make any sense.

Joey: Of course it does! It’s smart! I used a the-saurus!

Chandler: On every word?

Joey: Yep.

Monica: All right, what was this sentence originally?

Joey: Oh, “They are warm, nice people with big hearts”.

Chandler: And that became “They are humid, prepossessing Homo sapiens with full-sized aortic pumps”?

Joey: Yeah, yeah. And hey, I really mean it, dude.

– Friends (Season 10, Episode 5 – The One Where Rachel’s Sister Babysits)

As you can see, Joey’s overuse of a thesaurus causes him to turn out a ridiculous stream of long words that have nothing to do with what he wants to say. While Ross’s advice may have been good in theory, he probably should have warned Joey not to go straight for the “smartest sounding” word every single time. The problem wasn’t just that his letter would come out overly “purple“, but that there was an important tip he neglected to keep in mind when choosing synonyms: context is key.

A notable example of a misused synonym in the above dialogue is “humid”. As we all know, while “warm” and “humid” have comparable definitions when it comes to describing the weather, only “warm” is also applicable to people. A similar problem happens with the use of Homo sapiens, which is only good for scientific writing and doesn’t really work as an alternative for “people”. With all these big words so out of place, it’s no wonder Monica and Chandler couldn’t understand anything Joey had written!

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the full definition of a word before you try to pass it off as a replacement for a more common one, advice that many writers fail to take into account.

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the full definition of a word before you try to pass it off as a replacement for a more common one, advice that many writers fail to take into account.

One particularly embarrassing example of this practice from my own experience is when I used the word “fortuitous” incorrectly in a story. My thesaurus listed it as a synonym for “random”, but what I didn’t realize until after publishing the piece was that while “random” is a neutral word, “fortuitous” usually has a positive connotation (as in “good fortune”), which was not the feeling I intended to convey. Fortunately, no one ever called me out on it, but it was still embarrassing to know the mistake was out there for anyone to see. So to be safe, make sure you look up the definition of a synonym before you use it in your writing. You’ll be glad you did.

A thesaurus can be a friend or an enemy, depending on how much faith a writer is willing to invest in it. While its uses are mostly beneficial, it’s up to you to make sure that this trusted ally doesn’t turn on you and muddle up the meaning behind your words. It’s OK to trust your thesaurus to help you enhance the vocabulary in your writing. Just try not to use it in excess!

Monica: Hey, Joey, I don’t think we can use this.

Joey: Why not?

Monica: Well, because you signed it “Baby Kangaroo Tribbiani”.

What about you? Do you make good use of your thesaurus? Has it been more of a help or a hazard to your writing?

by Naomi L. | October 9, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Featured |

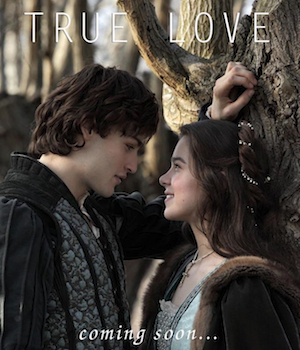

The new Romeo & Juliet movie is coming to UK and US theaters this Friday (which I admit makes me totally jealous, since there’s no set release date for where I live yet). In the spirit of celebrating one of William Shakespeare’s most famous plays, today’s topic is centered around this classic tale of love, fate and tragedy.

Douglas Booth and Hailee Steinfeld as Romeo and Juliet

Now I’m going to make a confession: I absolutely love this story. I love any story about forbidden love (as long as it’s well-told), and being the epitome of such a tale, Romeo & Juliet may be one of my favorites. In fact, I love it so much that I’ve read scenes several times over (yes, I read Shakespeare for fun, believe it or not), have actively sought out a fair share of adaptations, and have even used it as inspiration for my own romantic fiction.

But don’t mistake me for a silly fangirl. For the longest time, I believed the common interpretation that Romeo and Juliet were no more than two immature teenagers who recklessly rushed into a superficial relationship at the ultimate expense of their families and the rest of Verona. It wasn’t until I started researching in-depth analyses of the story (again, for inspiration) that I came to understand what I was missing in Shakespeare’s timeless classic, and what most modern readers/viewers might be missing too.

So to set your impressions straight before you head out to see this movie, here is a list of five points in Romeo & Juliet that you probably never noticed before. Get ready to see another side of this story!

(Warning: the following list contains possible spoilers for Romeo & Juliet. If you’re one of the few people on the Internet who are not familiar with this tragic story, proceed with caution. Or you can just read a full summary of the plot here.)

1) Rosaline is an important character

Before Romeo meets Juliet and falls desperately in love with her, he actually has his sights set on a different girl: Rosaline. In fact, his very first appearance in the play has him moping to his cousin Benvolio about the unrequited love he claims to feel for this unseen lady, and he even agrees to crash the Capulet ball with his friends just for the chance to see her.

But other versions of the story tend not to place very much importance on Rosaline. Most adaptations don’t even give her a face, and some exclude her character altogether, instead providing a different explanation for the Romeo character’s depression before he meets his Juliet (e.g. West Side Story: Tony longs for excitement in his life, which he finally discovers upon meeting Maria). This common alternative likely stems from the assumption that Rosaline’s only purpose in the original story is to lure Romeo to the ball so he can cross paths with Juliet, a plot point that can be easily worked around (continuing from the previous example, Tony first encounters Maria at a local dance that he only agreed to attend as a favor to his best friend).

Yet Rosaline actually plays a much greater role than a mere plot device. While pining for her, Romeo has a preconceived notion of what it means to be in love, and acts according to the lessons he’s learned from the hackneyed romantic poetry he likes to recite when thinking of her. At the first sight of Juliet, however, he abandons every thought of his former clichéd infatuation in favor of a much deeper passion that sparks some incredibly beautiful and original love poetry from his own heart (which, when you think about it, may have been Shakespeare’s way of saying “Take that!” to the poets before his time). To put it simply, the switch from Rosaline to Juliet is essential to highlight the main characters’ true feelings for each other by showing the audience the difference between Romeo thinking he’s in love and Romeo actually being in love.

Seriously, did Rosaline ever stand a chance against Juliet?

What you’re probably thinking: He takes one look at Juliet and forgets about Rosaline just like that? Damn, Romeo is so superficial!

What you should be thinking: Wow, Juliet inspires such beautiful passion in Romeo! He must really love her!

2) Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech is a warning

One of the many famous monologues in Shakespeare’s works is the Queen Mab speech delivered by the bold Mercutio in Act 1, Scene 4 of Romeo & Juliet. This is the scene in which he teases Romeo for pining after Rosaline and tries to break his illusions of love by delivering a lecture about the dreams of men and how they can ultimately lead to ruin. Sound familiar?

“True, I talk of dreams,

Which are the children of an idle brain” (1.4.97-98)

Mercutio starts by talking about Queen Mab, the mythical fairy queen who rides through the night bringing pleasant dreams tailored to every sleeping individual. But as he goes on, the lighthearted speech quickly takes a morbid turn into a downward spiral through darker visions of depravity (from lovers dreaming of romance to soldiers dreaming of killing), until finally culminating in a bitter yet accurate portrayal of society. Instead of taking from the speech a lesson about realism and the twisted nature of humanity, however, the idealistic Romeo simply disregards his friend’s words as another of his many mischievous taunts, silencing him with a single exasperated comment, “Thou talk’st of nothing.”

Like Romeo, modern audiences might be inclined to dismiss the Queen Mab speech as unnecessary rambling that contributes little to the rest of the story. Indeed, the monologue’s main purpose is to illustrate Mercutio’s wit and roguish nature, but it can also be interpreted as a critique against the romantic ideals that drive the play’s entire plot. In a way, Mercutio’s speech is foreshadowing the tragedies that will occur over the course of the story, and while it isn’t necessarily important, it certainly adds an interesting subtext to the themes of Romeo & Juliet.

What you’re probably thinking: Man, Mercutio really likes to hear himself talk!

What you should be thinking: Mercutio knew a thing or two about realism. Romeo probably should have listened…

3) Paris and Lady Montague even the score

Remember that part near the end of the story when Romeo kills the Count Paris in the Capulet tomb, and that other part when Montague says his wife died of grief after their son was banished from Verona? No? Then you must be familiar with any version of Romeo & Juliet other than the original play itself.

The fact is, most adaptations of this play tend to exclude the deaths of Paris and Lady Montague because they don’t contribute very much to the plot. The latter even goes virtually unnoticed, her offstage death being summed up in only two lines. So why would the playwright even bother killing these characters off in the first place?

Because it’s only fair. Before Romeo and Juliet famously take their own lives at the end, two other important characters suffer dramatic deaths in the middle of the story: Mercutio and Tybalt. But wait, wasn’t Mercutio on the Montagues’ side? Yes, but he was not a member of their family, as Tybalt was of the Capulets’. Mercutio was actually from the third noble family in the play: the Prince’s. This means that after all four of these characters die, the House of Capulet would technically have suffered the greatest loss.

Unless one more family member were to be lost from each of the other two houses. Enter Count Paris and Lady Montague. Paris, though aligned with the Capulets, is another kinsman to the Prince, and ends up being killed in a fight with Romeo during his visit to Juliet’s tomb while she’s faking her death. A little later, after the bodies are discovered in the tomb, the Prince calls forth the heads of the feuding households, at which point Montague accounts for his wife’s absence by explaining that the news of her son’s banishment ended up killing her.

Surprise: one of them might not survive the movie this time. Guess who.

Final death toll:

- Capulets – 2 (Juliet and Tybalt)

- Montagues – 2 (Romeo and Lady Montague)

- Prince – 2 (Mercutio and Paris)

Conclusion: everyone loses, but at least in perfect balance.

What you’re probably thinking: Six people die by the end of the story? Shakespeare was twisted! No wonder most newer versions cut out these deaths!

What you should be thinking: Wow, every house loses two loved ones? How sad!

4) The poison and the dagger are symbolic

Romeo: “Thy drugs are quick. Thus with a kiss I die.” (5.3.120)

Juliet: “O happy dagger,/ This is thy sheath. There rust and let me die.” (5.3.169-170)

If there’s one thing for which Shakespeare was notorious, it was his innuendos. Plenty of his works contain their fair share of double entendres and the like, and Romeo & Juliet is no exception. However, instead of covering every example in the play (which would take a while, especially for scenes involving Mercutio), let’s just skip ahead to the one hidden in the famous double suicide ending.

You know how Romeo kills himself by drinking poison when he thinks Juliet is dead, and then Juliet stabs herself with Romeo’s dagger after she finds his body? Well, guess what: those two items are not random, but were carefully chosen to secretly represent the lovers’ intimate relationship. Romeo’s weapon of choice comes in a cup, which is a symbol of femininity. In contrast, Juliet uses a blade, a symbol of masculinity, to take her own life. In this way, their deaths are meant to reflect the intimacy they shared in life, thus completing the play’s theme of love ending in tragedy.

Or it’s all just another product of Shakespeare’s deviant mind, depending on how you choose to read into it.

What you’re probably thinking: Shakespeare must have been a misogynist, to have Juliet suffer a much more painful death than Romeo.

What you should be thinking: Even their deaths symbolize their intimate love. Shakespeare was clever with metaphors.

5) Romeo & Juliet is a coming-of-age story

Now I know what you might be thinking: how can Romeo & Juliet be a coming-of-age story if the entire plot only happens over four days? Perhaps it’s not a coming-of-age story in the traditional sense, as the teenage protagonists never actually reach adulthood, but their characters do mature throughout the course of the play, from the moment they meet to their untimely end.

At the beginning of the story, Romeo and Juliet are little more than naïve adolescents, both fairly inexperienced in life and in love. As soon as they first cross paths, however, they quickly propel each other toward the maturity of adulthood. Upon meeting Juliet, Romeo sheds his superficial conceptions of romance to become one of the most truly passionate lovers in all of English literature, and it is this passion that drives his actions for the rest of the play. Juliet, in turn, draws strength from her love for Romeo to develop into a confident and levelheaded young woman, making shrewd observations (“You kiss by th’ book”) and logical decisions that balance out her lover’s spontaneity. The intense love that outweighs the hatred around them makes their marriage all the more pure, and their loyalty to one another drives them to choose an eternity together in death over a miserable life alone. In short, though modern interpretations mistake these young lovers for foolishly infatuated teenagers, in-depth analyses reveal the true qualities of their complex characters, bringing to light the real depth of Shakespeare’s classic story of “death-marked love”.

“For never was a story of more woe

Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.” (5.3.309-310)

What you’re probably thinking: They rushed into marriage after less than a day and then killed themselves because they couldn’t live without each other? Romeo and Juliet were so immature!

What you should be thinking: They were so young and they experienced such a grand romance. Romeo and Juliet were truly in love!

All caught up on these secret details?

Great! To leave you on a high note, here is the official trailer for the 2013 release of Romeo & Juliet (the original UK trailer can be found here). Enjoy!

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gp9yaZcrtnU]

Reasons I have high hopes for this movie:

- A screenplay adapted by Downton Abbey creator Julian Fellowes

- A stellar cast featuring talents such as Hailee Steinfeld, Douglas Booth, Ed Westwick, Damian Lewis and Paul Giamatti

- Good chemistry between co-stars Hailee Steinfeld and Douglas Booth

- Shot entirely on location in Verona and Mantua, Italy

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading about the secrets hidden in Romeo & Juliet! I understand that many will disagree with some of these points, but honestly, I think that’s part of the beauty of this tale: that it can be interpreted in so many different ways. To some, it’s a tale of love thwarted by fate; to others, it’s a warning about the dangers of being too impulsive. In any case, I’m sure we can all agree that this classic story has greatly endured the test of time, and will probably continue to intrigue admirers of Shakespeare and inspire the romantic at heart for generations to come.

On a final friendly note: kids, trust me when I say you do not want a romance like Romeo and Juliet’s! Yes, this is a beautiful story and a great one to read and learn from, but the story you want to live is that of Grandma and Grandpa, who had a life and grew old together. It’s important to know the difference!

Oh, and if anyone from the UK or US happens to watch this film, please let me know if it’s good. I’m very much looking forward to it. Thanks for reading!

(Disclaimer: All images and video in this blog post are courtesy of Swarovski Entertainment and Amber Entertainment. For news about the film, follow them on Facebook and Twitter. I own nothing; I’m just a fan hoping to spread the love. Thank you!)

by Naomi L. | August 21, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Featured, Tropes |

*click*

Have you ever read a story or watched a movie/play where you noticed a certain item being used as an important plot device in a major scene, only to realize that the object in question had already made an appearance in a previous scene as some seemingly insignificant prop in the background?

Well, what you witnessed was the figurative (or in some cases, literal) firing of a Chekhov’s Gun.

The Loaded Rifle on the Wall

The Chekhov’s Gun is a literary technique that places significance on a certain story element that was introduced earlier on as an unimportant detail. The trope is based on a dramatic principle conceived by Russian playwright Anton Chekhov (1860-1904), which states that every detail presented in a story must either be necessary to the plot in some way or removed from the narrative altogether.

If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.

– Anton Chekhov (S. Shchukin, Memoirs. 1911)

It’s important to note here that a Chekhov’s Gun is not necessarily an actual gun; the playwright’s example was merely used in reference to live theater, where a loaded gun on stage would pose an unnecessary safety hazard if it wasn’t going to be used as anything more than a background prop. Rather, the device is a metaphor for any element of a story that can become important later on. It doesn’t even have to be an object; it can just as easily be a character, a skill, a line of dialogue, etc. A full list of possibilities and variants can be found at the TV Tropes Chekhov’s Gun Depot.

Handling a Chekhov’s Gun in Your Writing

There are two main concepts connected with this trope:

- Conservation of Detail – Every detail presented in a story has an important reason for being there

- Foreshadowing – A detail given early on is an indication of a plot point that will happen later in the narrative

While a Chekhov’s Gun should really be used with the former concept in mind, it’s most commonly associated with the latter. Writers will often use this trope as a tool to indicate upcoming events in the story, usually in a subtle manner that goes virtually unnoticed the first time around and becomes clear after the revelation of the foreshadowed plot point.

So how should you use this technique in your own stories? To properly execute a Chekhov’s Gun, the element in question must have some level of presence established in its introduction, not necessarily so much that it gives away a potential plot twist, but enough that the audience will realize it was there all along by the time it becomes significant. This will keep your readers from assuming you pulled some random solution out of thin air to hastily tie the plot together at the end, and thus prevent you from evoking their disappointment.

Also, bear in mind that there is such a thing as too many Chekhov’s Guns in one story. While you shouldn’t feel limited to just one per narrative (and many writers aren’t, myself included), you should still take care not to go overboard with the trope. Of course, these limits may vary depending on the type of work in which it’s used; for example, fantasy sagas or mystery thrillers may depend heavily on these devices to help drive the plot (as seen in the Harry Potter series, which even has its own Chekhov’s Gun page on TV Tropes), whereas simpler action stories could work just fine with only a couple at most. So if you’re planning to write long narratives full of twists, you might be able to make good use of this technique throughout the entire story arc. It’s worth noting, though, that if the plot becomes convoluted enough, your readers might eventually start looking for significance in the tiniest details to try to find Chekhov’s Guns that you may or may not have placed in your story. But then again, maybe that’s exactly what you want.

The Chekhov’s Gun can be a useful device in fiction, provided it’s used correctly and in proper tone with the story. Whether you choose to use this technique for major plot points or just to add some interesting twists, be sure to always keep in mind the importance of only including details with a given purpose, and you’ll be able to build a narrative that highlights the plot and tells a story that can be freely complex on the surface while remaining simple and straightforward at its core. And that, in my opinion, is the best type of story a writer can create. Happy writing!

*BANG!*

by Naomi L. | July 24, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Featured, Tropes |

I’m polymerized tree sap and you’re an inorganic adhesive, so whatever verbal projectile you launch in my direction is reflected off of me, returns on its original trajectory, and adheres to you.

– Dr. Sheldon Cooper, The Big Bang Theory (Season 1, Episode 13 – The Bat Jar Conjecture)

Fans of the comedy TV series The Big Bang Theory likely remember this quote from the Physics Bowl episode, when Sheldon reacts to an insult from fellow physicist Leslie Winkle by saying as condescendingly as possible that “he is rubber and she is glue”. However, the fact that he seems to go out of his way to use the most advanced vocabulary possible in his retort only adds to the hilarious running gag of Leslie always managing to beat her rival at a game of wits.

So what lesson should novice writers be learning from Sheldon’s backfired comment? That trying too hard to sound smart often has the opposite effect than what you might expect, that is, it hurts more than it helps.

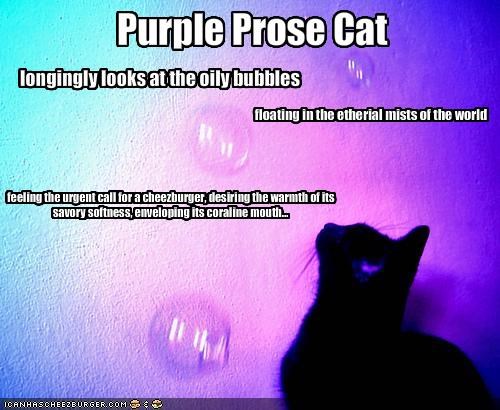

What is this amethystine composition of which you speak?

Writing that is overly decorated with fancy words and elaborate details is known as “purple prose”. It’s an especially common practice among inexperienced writers, who often believe that to write a really good story (or improve upon an existing dull one), one needs to dress up the prose with as many big words as possible to make their work look sophisticated. Basically, beginners seem to have this grand illusion that great literature is that which stands above the level of everyday speech.

Purple prose: Contemplate this exquisite aubergine blossom of the Rosaceae family

Everyday speech: Look at this beautiful purple rose

But here’s the problem with that logic: everyday speech is the level where most readers are, and more importantly, where they want to stay. Readers today don’t want to bore their way through long descriptions or have to pause at every other page to look up half the words they just read in the dictionary. They want writing that’s simple, that they can understand and find relatable, similar to the language they use themselves in the real world.

So I’ve been writing erroneously… I mean, wrong all this time?

Calm down, and take a second to note that I said “similar to”, not “the same as”. It’s OK to use some higher-level vocabulary and detailed narration in your stories, for when done in moderation and in tone with the style of the work, these can actually add to the quality of your writing. The danger is using these tools in excess, because after you’ve passed a certain point in flowering up your prose, these details will begin to draw attention to themselves and away from the flow of your story. To sum up, a little is fine, but too much is bad. Write with caution.

Now before anyone accuses me of hypocrisy, allow me the chance to admit to this embarrassing fact: I am guilty of writing purple prose. Even if I don’t always choose the fanciest synonyms I can find to replace everyday words, I love decorating my writing with adjectives and adverbs, and I tend to use intermediate-level words where common ones would work just fine. That being said, I used to be much worse. When I first started writing, I had this idea that nobody would want to read stories written in the plain language of a ten-year-old, so even though I was already well-read for my age, I went out of my way to find “bigger and better” words for my fiction. It wasn’t until I started learning about common writing mistakes as a young adult that I realized how flowery my early writing was, and I’ve since been gradually cutting the bad habits of my childhood. So take it from a writer who’s still breaking out of the novice phase: tone down the purple and focus on writing simple prose. Your readers will appreciate it.

It’s worth noting at this point that as strongly as most experienced writers will argue against this practice, prose style is and always will be subjective. It’s entirely possible for a writer to not only be aware they write such elaborate prose, but actually do it on purpose. So if you’re a beginning writer guilty of this trope, don’t feel bad right off the bat. Maybe your goal is to imitate the exact styles of writers like William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens and Jane Austen, and that’s fine. Just know that unless you’re going for satire, most of the audience who would take your work seriously has probably been dead for a few hundred years.

It’s worth noting at this point that as strongly as most experienced writers will argue against this practice, prose style is and always will be subjective. It’s entirely possible for a writer to not only be aware they write such elaborate prose, but actually do it on purpose. So if you’re a beginning writer guilty of this trope, don’t feel bad right off the bat. Maybe your goal is to imitate the exact styles of writers like William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens and Jane Austen, and that’s fine. Just know that unless you’re going for satire, most of the audience who would take your work seriously has probably been dead for a few hundred years.

But I want to be taken seriously today! What should I do?

Don’t worry, the “purple prose bug” is treatable! For those of you aspiring writers who wish to establish yourselves before you try to follow the great authors who bend the rules, here’s a quick list of common purple prose mistakes and how you can avoid them:

1) Excessive detail. Yes, describing the setting of a scene before the action starts is often essential to telling a good story, but please don’t go on for a dozen pages about the hundred different colors in the sky or the history hidden in every brick of every building. Just because authors like J.R.R. Tolkien and Victor Hugo could get away with it doesn’t mean you can. One paragraph should be enough to set your scene, but no more than two.

2) Overly decorated nouns and verbs. If you’re one of the millions of readers who have read all of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books, you may have learned that nouns and verbs should almost always include a “modifying friend”. But Rowling is an exception, a world-famous author of one of the best-selling book series in history, which you are (probably) not. That means she can do whatever she wants with her writing, whereas you should practice creating basic prose before you work too hard to copy her style. Try not to use too many adjectives and adverbs in your writing. Though this may seem counterintuitive, many famous writers would agree that less is more. If you don’t believe so, read a story by Ernest Hemingway or Mark Twain, and you’ll see how writing can be great without the need for too many “attachments”. To quote Twain, “When you catch an adjective, kill it.”

3) Said bookisms. This is one of the most common mistakes made by beginning writers: the constant use of alternative verbs for the word “said”. There’s a general belief that when it comes to writing dialogue, “said” is too plain and overused, so writers should go out of their way to replace it with words like “asked”, “muttered”, “hissed”, etc. As a teenager, I used a lot of these in my writing; I wouldn’t be surprised if I read back a dialogue-heavy scene from one of my old stories and found at least three pages between consecutive uses of “said”. But even famous authors seem to be guilty of this sometimes (I’m given to understand there’s an entire blog devoted to poking fun at the purpleness of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series), so don’t feel too bad if you find your own writing full of these bookisms. The important thing is that you know you should fix them. Dialogue should convey tone by itself, no extra tags required.

4) Too much “fancy vocabulary”. Continuing from the example of “said”, some writers tend to try and find as many advanced-sounding synonyms as possible to substitute the common words in their stories. While this may be fine once in a while, you shouldn’t run to the thesaurus for every other word you want to write. Otherwise, you’ll end up sending your readers to the dictionary just as frequently. It’s great to learn new words, but think about it for a second: the more time you put into driving your audience to read another book, the less time they’ll spend reading yours. Try to stick to vocabulary that your readers will understand, and if you must throw in a higher-level word now and then, at least have the courtesy to make its definition clear in context.

5) Exaggerated sentiment. There isn’t a lot I can say here except that this is pretty much a writer’s attempt to manipulate the reader into reacting a certain way to their writing. Going back to the first item on the list, if you throw too much rhetorical writing into your stories, it comes across as you trying too hard to evoke specific emotions from your readers, which more often than not will have the opposite effect. Trust your audience to understand what you’re trying to tell them. If you write it plainly enough, they will feel it.

Purple prose is a dangerous habit of many writers, and while it may be OK for some, most should make a point of avoiding or overcoming it, no matter how difficult this seems. If nothing else, choosing to create simple and clean prose is a sign of respect to your work and your readers, so take care with your style of writing. I’m certainly still trying.

So what are your experiences with purple prose? Have you read stories that you found too flowery for your taste? Were you (or are you) ever guilty of making these mistakes yourself?

by Naomi L. | May 1, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Featured, Writer's Toolkit |

Every writer who is serious about their craft needs to have a well-stocked writing toolkit at their disposal. Of course, the exact tools may vary among the different artists who choose to use them: a poet may use only small notebooks for jotting down his thoughts, while a short story writer may also choose to keep index cards for organizing her ideas, while a novelist may have a whole bulletin board (or even a room full of them) for keeping track of elaborate plots. Some tools can be seen as universal necessities to all creative writers (such as journals and the aforementioned notebooks), and others seem to be more of a personal preference (such as index cards and exercise books).

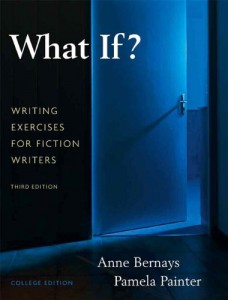

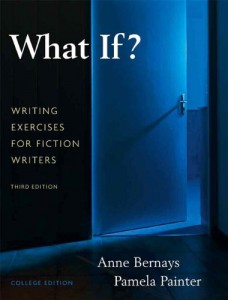

In the interest of exploring this array of choices, I’ll be telling about my experience with the instruments in my own writer’s toolkit, starting with a fantastic book of fiction exercises that has proven to be a valuable asset to me: What If? Writing Exercises for Fiction Writers, by Anne Bernays and Pamela Painter.

What If? Writing Exercises for Fiction Writers, by Anne Bernays and Pamela Painter

About the Book

I bought this book for the online creative writing class I took through UC Berkeley back in 2011. The copy I own is the third edition, also called the college edition, which was released in 2009. It holds 109 exercises covering 13 different topics, plus 11 short short stories and 14 short stories provided at the end of the book. Also included with every exercise description is an explanation of the objective behind it, as well as the occasional example courtesy of the authors’ students.

The topics (or parts) covered in the book are:

- Beginnings;

- Characterization;

- Point of View, Perspective, Distance;

- Dialogue;

- The Interior Landscape of Your Characters;

- Plot;

- The Elements of Style;

- A Writer’s Toolbox;

- Invention and a Bit of Inspiration;

- Revision: Rewriting is Writing;

- Sudden, Flash, Micro, Nano: Writing the Short Short Story;

- Learning from the Greats; and

- Notebooks, Journals, and Memory.

So what can I tell you about the book? Here are a few key points I’ve learned from my experience.

Pros

The diversity of topics in the book allows you to “custom improve” your writing in the areas you feel need the most work. The explanations are easy to understand, and the student examples are excellent models of the techniques taught through the exercises. For a truly well-rounded experience, a friendly introduction by Bernays and Painter encourages all readers to explore the potential of their writer’s voice and explains the separate definitions of writing like a writer and thinking like one, while the last two sections provide 25 excellent stories to better illustrate the points made throughout the book. Needless to say (oops, Exercise 51: “Word Packages are Not Gifts”),What If? covers a wide enough spread to make it an excellent resource for any fiction writer, as much for the beginner in need of good practice as for the seasoned writer looking to rekindle the fire of inspiration.

But nothing is perfect, right? Now for the downsides…

Cons

The main obvious drawback about using What If? is that it practically requires sharing of completed exercises and subsequent receiving of critique in order for its readers to get the full intended benefits of the book, making it a more popular choice for creative writing workshops and courses as opposed to individual study. Aside from this, readers might find a couple of topics to be lacking in sufficient exercises (Part Seven, for instance, only contains four), which might put off those hoping for a more diverse selection within a certain module. Also, not every written exercise comes with an example, leaving it solely up to the practicing writer to determine the intended approach to the exercise. This is fine for the more independent readers, but for those often looking for extra guidance (like me), it might prove to be a bit of a disappointment.

Still, I honestly don’t think these minor cons do much to outweigh the stronger pros. Yes, What If? is not without its flaws, but overall, I feel it’s a worthwhile read that warrants a place on any writer’s bookshelf.

Summary

Pros

- Wide diversity of topics (13 total)

- Exercise descriptions that are easy to understand

- Excellent student examples

- Friendly and comprehensive introduction

- 25 short stories

Cons

- Requires feedback for full experience

- Limited selection of exercises in some topics

- Lack of examples in some exercises

Conclusion

Why have I chosen to open my Writer’s Toolkit posts with this book? It wasn’t a matter of random choice, but rather one of relevance to my own writing. Many of the pieces I’ve written (and others which I’m currently writing) blossomed from the exercises contained in this book, and because of the enlightenment and fun I’ve had with them so far, as well as my need for critique from other writers, I decided to make a habit of sharing some of my own examples of attempts to complete them.

So whenever a certain piece I share in the future has been inspired by a What If? exercise, I’ll be sure to provide a brief explanation of that exercise for easier reference. However, if you’re a writer and you don’t have this book, I highly recommend that if you have the time (and the funds), you grab yourself a copy of What If? as soon as you can! You won’t be disappointed.

There you have it: the top creative writing book on my shelf, and one of the most useful resources in my writer’s toolkit. I hope you’ll enjoy the pieces I produce from these exercises, and I also invite you as aspiring writers to try them out for yourselves. In fact, if you have writing blogs of your own, by all means, please share links to your own pieces in the comment sections. I would love to read them! In the meantime, please feel free to offer your feedback on my work; I look forward to receiving constructive opinions that would help me to further improve my writing.

Thanks for reading! Happy writing!

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the full definition of a word before you try to pass it off as a replacement for a more common one, advice that many writers fail to take into account.

But there’s another problem with placing too much trust in a thesaurus. Although the purpose of the guide is to index words with similar definitions, there’s a catch: the “synonyms” that come up don’t always have the exact same meaning. This means you should always be aware of the full definition of a word before you try to pass it off as a replacement for a more common one, advice that many writers fail to take into account.

Recent Comments