by Naomi L. | July 17, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing |

I love TED Talks. From science to politics to social topics, they’re always inspiring to watch, and they’ve opened my eyes to quite a few fascinating perspectives in a wide array of global issues. But one Talk that really – if you’ll pardon the pun – spoke to me as a creative and soft-spoken individual was author Susan Cain‘s take on the power of introverts.

This video was shared with me some time ago by my best friend, a young man just as introverted as I am who found this Talk very inspiring for people like us (and those who wish to understand us). Instead of running through the entire 19-minute transcript, I thought it more convenient to embed the video here for others to watch themselves. Enjoy!

(Note: in case it doesn’t load properly on the page you’re reading, you can watch the Talk on its original TED page here, where you can also find a full transcript).

[ted id=1377]

Since there isn’t much I can add that Mrs. Cain hasn’t already covered perfectly well, I just want to give a brief review of how I can personally relate to her Talk and the ways I consider her case valid to my experience in creative writing.

Avid reader

I too spent much of my childhood reading books. Although most of my reading time was in the privacy of my own bedroom, I did make a habit of carrying books in my backpack to enjoy at school. Whenever I felt exhausted by the energy of my surrounding classmates (which was quite often), I would find a quiet corner and retreat into the world of my books to recharge. Maybe it seemed like an overly reclusive practice, but in a way, my books were like a lifesaver that helped me through my grade-school years.

Introversion vs. Shyness

I’m glad Mrs. Cain brought up this distinction, as it’s important to know there’s a difference. A great example of this is my dad: he’s one of the most social and friendly people I know, but when it comes to work, he much prefers handling tasks on his own. My dad is what some might consider an unusual type of individual: an outgoing introvert.

Having noted this, I’d like to point out that I’m both introverted and shy. The main difference is that my shyness is a trait that I’d like to be able to overcome, at least to the point where it no longer holds me back from doing most of the things I’d like to try in my life; whereas my introversion is a characteristic that I will always be proud to consider an important part of my personality. In other words, I’m not always happy about being shy, but I am always happy about being introverted.

In the classroom

At the risk of sounding boastful, I was an excellent student growing up. I’m talking straight-A, perfect-record, all-my-teachers-loved-me excellent. And I honestly believe that my introverted personality played a major role in my academic achievements. That’s not to say that extroverted students were beneath my level; my best friend in middle school was an extrovert, and she was in the gifted program with me. My low-key approach to my studies just worked best for me because the time I used to work on my own allowed me to think much more clearly.

However, I do remember some classes I took in elementary and middle school where the desks were arranged in the pods described in the above video, so I’d have to be facing at least three other students and often work with them in group assignments. I understood the point of this arrangement, but to be frank, I much preferred the rows.

Solitude = creativity

I agree with the speaker’s argument that we shouldn’t stop collaborating altogether, nor should we stop valuing the great qualities that extroverts bring to the table, but we should at least have a decent balance between teamwork and solitude, since the latter is often important for creativity to blossom. I’ve always found that my best ideas come to me whenever I’m alone with my thoughts, especially when I have plenty of time to daydream (one of my favorite pastimes). But I know that writing isn’t a completely solitary profession, which brings me to my final point…

The budding writer

I love creative writing for the freedom I feel it gives me. I’m in total control of my ideas, my characters, my settings and plots. But there’s only so much enjoyment I can get out of writing on my own, because after I finish shaping my ideas into my stories, I can’t wait to share them with the rest of the world, and that requires stepping out of my introverted shell.

I know that after I finish my novels, I’m going to have to put them out there somehow, helping to promote them and get them to the readers that I want to inspire. And I think I’m OK with that. As long as I still get to be my introverted self (and be appreciated for it), I’m OK with having to face the extroverted lifestyle once in a while for the sake of that all-important balance for which Susan Cain so strongly advocates. Looking up to the countless introverts who have graced the world with their amazing qualities, I hope to have equal courage to – as she so wonderfully puts it – speak softly.

What about you? Are you an introvert or an extrovert (or an ambivert)? How well can you relate to Susan Cain’s Talk? Do any of these notes apply to you?

by Naomi L. | July 10, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Writer's Toolkit |

I realize I haven’t written a Writer’s Toolkit piece since my review of What If? Writing Exercises for Fiction Writers. For my second post in this topic, instead of a specific book, I’ve decided to write a brief review of the importance of a more general tool that every serious writer should have at their disposal: a personal journal.

Writer’s Journal

I’m sure we all remember the innocent grade school days when the most trustworthy friend we had was that little book sitting in our bedroom, whose sole purpose was to guard our deepest thoughts and feelings. Many of us at one time or another have owned a notebook of some sort that we kept as a diary or journal (I myself kept quite a few during my childhood and adolescence). It was our outlet for the private ideas we couldn’t share with anyone else, an emotional release that left us with the satisfaction of knowing our secrets were still safe from the rest of the world. But for the budding writers among the countless young people pouring their hearts out in secret, that book was so much more. While all the other children and teenagers would keep their journals and diaries as a vent, we writers would keep them as a net to catch the little seeds dispersed throughout our lives that could eventually grow into our stories.

A journal is an important tool for any writer mostly because it serves as a log of the potential story ideas that might otherwise elude us. To give a personal example, during my college years, I kept a journal in my backpack in which I would write the thoughts and emotions I experienced while at my university. The book was a record of my college life, and several of its entries – about which I might otherwise have forgotten – later became inspiration for my fiction writing. Without that journal, I likely would have missed a lot of opportunities to find relatable traits for my characters or interesting scenarios for stories.

But my journals have helped me in an even greater capacity. Writing down my thoughts and being able to read them back objectively has allowed me to gain a better understanding of how I tend to see the world around me, and consequently, learn how I can best channel my ideas into my writing. On top of that, while my fiction pieces are for showcasing my refined writer’s voice, my private journals are for unleashing the raw voice fresh out of my mind that has yet to be shaped into the stories I want to tell. As I’ve come to realize, even creative writing comes with basic rules when intended for other readers, but when writing just for yourself, there are absolutely no limitations except you.

Summary

Advantages of Keeping a Journal

- Intellectual and emotional release

- Keep a record of possible ideas for future stories

- Objectively observe and understand the voice(s) in your head

- Unleash your raw creativity without inhibitions

Based on my experience (as well as similar accounts from other more established writers, including authors to be mentioned in future Writer’s Toolkit posts), I highly recommend keeping a personal journal as a good exercise for any writer. Sure, many of us probably don’t have the time to fill half a dozen journal pages (or even one) every day, especially in these modern times of ultra-busy lives filled with a hundred daily tasks that leave us exhausted by the time we get a chance to crawl into bed. Still, it’s good practice to set aside at least a few minutes every day to jot down some key observations of recent events, no matter how simple. Remember, even if your thoughts don’t seem particularly interesting at the time of writing, you never know if they could prove useful in the future!

Thanks for reading! Now, if you haven’t already done so, go and start your journal! Happy writing!

by Naomi L. | July 3, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Tropes |

Confused about the title? Or maybe you’re confused about my asking if you’re confused about the title? Or maybe you’re confused about my asking if you’re confused about my asking if you’re confused about the title? Or maybe you’ve had enough if this nonsense and just want me to get to the point?

This week’s creative writing topic is an interesting trope of which I’ve become rather fond over the course of my own writing: a technique known as “lampshade hanging“, or simply “lampshading”. It’s an idea I first learned about when reading TV Tropes, and because of the way I often see it being employed in humorous writing, it’s quickly becoming one of my favorite devices in fiction. But you probably don’t care yet what I think about it; you’re just waiting for me to explain what it is so you can decide whether you’d like it too. Unless you went ahead and skipped to the next paragraph before reading this one and already realize how I’ve been incorporating the trope into this blog post. Am I right?

This is not the lamp you’re looking for…

OK, no more stalling. Lampshade hanging is a trick employed by writers to address any noticeable implausibility or obvious trope usage in a plot by drawing attention to it… and then moving on. But wait, why would you want to point out your story’s flaws in the first place? Counter-intuitive as it may seem, this exercise does have a few advantages:

- It proves you aren’t trying to get away with a questionable plot development by showing your audience that you’re also aware of the absurdity;

- It establishes a sense of realism in your story by demonstrating that your characters are just as skeptical about the implausibilities in the plot as the real-life people following it; and

- It’s a way to beat critics to the punch of deprecating you for the “mistakes” you already know are in your story.

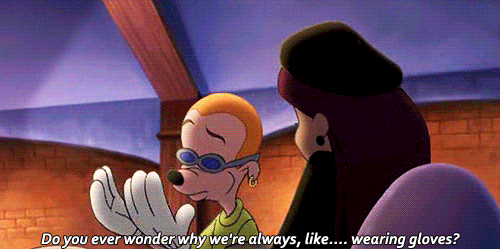

Need an example? Here’s a rather brilliant one from my favorite moment in the 2000 Disney film An Extremely Goofy Movie, when Bobby Zimmeruski randomly realizes something strange about the world around him…

You know you’ve always wondered the same thing…

The best part? This question is almost immediately dismissed and never comes up again for the rest of the movie!

It should be noted that whenever a writer “hangs a lampshade” on a particularly glaring plot hole, it could be taken as a hint from their subconscious about the true extent of an unforgivable absurdity in an otherwise serious work. Of course, the technique can also be observed in use to the extreme in stories that are intended to be especially humorous and even self-aware, which (when done well) can be very entertaining (like in this product placement clip from the comedy TV series 30 Rock, which brilliantly demonstrates Tina Fey’s mastery of humor tropes). Mostly, though, it works just fine when used in moderation, kind of like a brief comic relief to complement the action in the rest of the story.

Bonus note: aside from “lampshades”, the practice is also known as hanging a “red flag”, “lantern”, or “clock”. The trope is referred to as “lampshade hanging” in my blog because it’s the most common term used on the TV Tropes website, which in turn attributes the phrase to Mutant Enemy.

While I don’t hang lampshades often in my fictional works, I do enjoy throwing them into my blog posts now and then, which I tend to use for humorous purposes as a personal reminder not to take myself or my writing too seriously (a flaw of which I’m painfully guilty, possibly evidenced by the fact that I don’t like to end phrases with prepositions). Hopefully my readers find them entertaining, or at the very least, tolerable. I do enjoy practicing lampshade hanging, and if you like to keep an element of comedy in your own writing, you might like to take it up too!

Now if you’ll excuse me, I must go do extensive research for the next blog topic on which my novice writer’s knowledge is still relatively limited. Thanks for reading!

by Naomi L. | June 26, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing |

I don’t usually like to get picky about grammar, save for when I’m editing my own writing (or teasing my closest friends). Every now and then, however, I catch a few minor “mistakes” in the writing and speech of others that jump out at me. I use quotation marks because they aren’t necessarily wrong; I just tend to find them a bit odd, and occasionally a little annoying. Maybe there are others who would agree, and maybe sometimes it’s just me being my regular nerdy self.

I don’t usually like to get picky about grammar, save for when I’m editing my own writing (or teasing my closest friends). Every now and then, however, I catch a few minor “mistakes” in the writing and speech of others that jump out at me. I use quotation marks because they aren’t necessarily wrong; I just tend to find them a bit odd, and occasionally a little annoying. Maybe there are others who would agree, and maybe sometimes it’s just me being my regular nerdy self.

Just for fun, today’s topic brings you three random “pet peeves” of mine that are widely accepted as understandable language. You can decide for yourself where you stand on these…

1) When “could” really means “couldn’t”

I admit that it bothers me a little to see people using the phrase “I could care less” when they clearly mean to say “I couldn’t care less”. The logic behind the phrasing is simple: if you “couldn’t care less”, you’ve reached the limit of how little you can care about something, whereas if you “could care less”, there’s still a little part of you that does care and has yet to be eliminated.

I’ve heard a couple of theories as to how the “could” variation emerged in colloquial speech. One states that it was originally meant to be used in a sarcastic manner and not taken literally. Another explanation, according to American linguist Atcheson L. Hench, is that slurred speech has garbled the “couldn’t” of the correct phrase into the “could” that most people hear (American Speech, 159; 1973).

Which explanation is the truth? I have no idea. All I know is that I always use the original phrasing in my own speech, and if anyone doesn’t believe me when I say it’s the “correct” form, I couldn’t care less.

2) The American pronunciation of “niche”

I’ve lost count of all the playful arguments I’ve had with my best friend over this word. Our debates usually play out the same: I tell him the correct pronunciation is “neesh”; he answers back that people say “nitch”. I explain that the word comes from French, so its original pronunciation should be maintained; he argues that we’re American and we should adapt to the way most Americans speak. I ask him if by that logic, we should also start saying “ba-LET” and “gor-MET”; he claims that’s not the same thing because everyone says “ba-LAY” and “gor-MAY” without a problem. Then we toss the word “niche” back and forth, each of us insisting that our pronunciation is correct, until we both get tired and agree to disagree before changing the subject. After the entire discussion is over, we’re still friends.

Albeit friends who each still think they’re right. (Neesh.)

3) The alternative spelling of “doughnut”

To be fair, this one is more of a personal preference than an actual pet peeve. I understand that both “doughnut” and “donut” are equally acceptable spellings; I just prefer the former because it seems to me – for lack of a better description – “more correct”. It is the original spelling, after all; the invention of doughnuts can be traced back as far as the 19th century, but the earliest known printed use of the word “donut” is only from 1900 (Peck’s Bad Boy and His Pa by George W. Peck). Not to mention, “doughnut” also feels more complete: just by looking at the word, you can already tell what the main ingredient is…

Still, both spellings are equally pervasive in American English, though “doughnut” seems to be the more common form outside of the United States. Oxford Dictionaries list “donut” as the alternative spelling of “doughnut”, making the longer word the traditional option for more formal writing, yet the shortened form is popular for references like company names (e.g. Dunkin’ Donuts). Even my best friend (yes, the same young man who advocates so strongly for “nitch”) insists that “donut” is the best spelling because it’s modern, and thus more appealing to the readers of today. As he says whenever I insist that “doughnut” is the better choice, “Take it up with The Donut Man!”

These are just a few random examples of minor deviations from my grammatical standards. Like I said, they aren’t really wrong; it’s all a matter of preference. And call me a geek if you like, but I simply chose the alternatives that I deemed grammatically correct.

So what about you? Can you relate to any of the examples listed above? Do you have pet peeves of your own that don’t really detract from communication more than they just annoy you?

by Naomi L. | June 19, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing |

Once upon a time, there was a beautiful princess who lived in a dark castle guarded by a fire-breathing dragon, always dreaming of the day a young man would come and rescue her from the evil sorcerer who had kidnapped her and trapped her there. One day, a brave knight stormed the castle on his trusty steed, slew the dragon and killed the sorcerer. He rescued the princess from her lonely tower and took her back home to her kingdom. The king and queen were so grateful to the knight that they offered him their daughter’s hand in marriage, to which he and the princess gladly agreed. The knight and the princess were married, and they lived happily ever after. The End.

This is a classic fairy tale formula: villain has damsel, hero goes after damsel, hero defeats villain, hero and damsel fall in love and live happily ever after. The exact course of events may vary from story to story, but the basic idea is usually the same. Also universal in romantic fairy tales, if you’ll notice, are the character archetypes present in the plot. So pervasive are they in fiction that we’ve been trained from childhood to recognize them on sight: the handsome prince or the knight in shining armor; the beautiful princess or the young lady in need of rescue; the evil villain who stands in the way of true love, etc. And while these characters clearly serve their purpose when it comes to telling a well-rounded story, we as writers must ask ourselves why they don’t (or at least shouldn’t) appeal to us as satisfactory vehicles for the tales we wish to tell.

The main problem with the fairy tale characters is that they’re “plug-in” types. They’re like mass-produced instant ramen noodles: conveniently cheap and easy to prepare, but not exactly a healthy choice. When basic character profiles are used excessively over the years, they inevitably become clichéd and uninteresting. And intelligent readers don’t want clichéd and uninteresting; they want to see through the action on the pages to glimpse another level of the characters. They want depth.

The main problem with the fairy tale characters is that they’re “plug-in” types. They’re like mass-produced instant ramen noodles: conveniently cheap and easy to prepare, but not exactly a healthy choice. When basic character profiles are used excessively over the years, they inevitably become clichéd and uninteresting. And intelligent readers don’t want clichéd and uninteresting; they want to see through the action on the pages to glimpse another level of the characters. They want depth.

As writers, we are obligated to act as intelligent readers of our own works, even super-intelligent. We need to have a complete understanding of our characters that transcends our readers’ perceptions. To achieve this, we have to provide our characters with personal details that make up a life outside of the main action in the story, a life that will save them from being labeled as “ordinary” and keep our readers intrigued. So how exactly do we manage this?

Amelia stared out of the window of her room for what the scratched-up wall behind her claimed was the thirty-second day in a row. Yet again, she found herself longing to visit the rolling hills in the distance. It was so boring in her room: all the walls had already been painted twice in a dozen different colors, and she was out of embroidery supplies for the third time that week. She wanted to go outside, where there was fresh air and animals to chase and adventures to be had every day. She wanted her freedom back.

Good fictional characters are like real people: unique. They have backstory, flaws, fears and dreams. The best ones also have personal goals that often serve the important purpose of driving their stories forward. Can you think of anyone else who might fit that description?

Petrus, the lonely philosopher that she liked to visit on occasion, had foolishly thought it would be a good idea to get a small pet dragon to keep him company in his otherwise abandoned castle at the far edge of the forest. The second Amelia had stepped through the gate, the darn beast had chased her across the courtyard straight into the building, where her friend had told her that until he could find a way to subdue the dragon, she would have to stay inside where it was safe. That was a month ago.

Something I’ve noticed that I tend to do a lot when writing fiction is insert elements of my own personality and ideals into my stories. Although its usually done subconsciously, I feel this has helped me tremendously when trying to create believable characters. It isn’t just me, of course; many of the stories I’ve read seem to reflect characteristics of the writer behind them, as much the favorable as the less-than-flattering. Speaking from my experience, not only is this a practice that’s probably very common among knowledgeable writers, but that should really be encouraged among beginners, especially those who are prone to following the flat “Once upon a time” formula.

Jack couldn’t remember how he had ended up here. One minute, he was standing atop a tree beside a stone wall, trying to figure out where he was after being lost for an hour; the next, he was waking up in the courtyard on the other side of the wall next to an unconscious dragon and a huge broken branch. Before he knew it, an old man in a dark robe and a young girl his own age had run out of the nearby castle and were thanking him for his heroic deed. What heroic deed? Jack insisted he was no hero; he was just a squire who’d gotten lost after being separated from the knight with whom he was traveling to the kingdom. Nonetheless, the philosopher was grateful for this stroke of good luck, and requested that Jack accompany Amelia back home. She knew the way, he assured the boy, and her father was sure to reward him handsomely for his deed. The man was, after all, an advisor to the king himself…

Writing yourself into your stories has a few major advantages:

- It makes it easier to write in a way that readers will find relatable;

- It helps you develop a better familiarity with the characters you’re creating (after all, who knows you better than you, right?); and

- It allows your readers a subtle means of getting to know the writer behind the words.

The story shared here is just a silly fairy tale twist that I improvised, but which still serves to demonstrate how I tend to base elements of my writing on myself. Amelia’s painted walls and embroideries reflect an artistic side, though the adventurous dreamer in her is also a comment on my idealistic views about women who are independent thinkers. Petrus, being a philosopher, is a type of character who’s expected to be intelligent, but who still isn’t immune to bad decisions brought on by negative emotions like loneliness (why else would anyone get a pet dragon if they had no clue how to handle it?). Even Jack is a quirky character of humble status who would hardly consider himself a hero had he not been in the right place at the right time.

The traits I’ve taken from myself give all these characters a certain depth that separates them from their two-dimensional parallels in the first story and (hopefully) makes the second story a more interesting read. In this way, by writing yourself into your own stories, you can add color to your characters’ profiles and create tales that not only appeal to your intelligent readers, but also give them a chance to catch glimpses of the unique person that is you.

Amelia bid Petrus farewell as he fettered the unconscious dragon, thanking him for taking such good care of her for the past month. She then led the way to the nearby kingdom that was her home, and after reuniting with her worried parents, she introduced Jack as her new friend. The boy was awarded knighthood for taking down a dragon and saving the advisor’s daughter, and he and the girl quickly became best friends. For several years, Jack and Amelia continued to visit Petrus together and pursued many adventures throughout their adolescence, until at last they reached adulthood and realized they had fallen in love. The two friends were eventually married, knowing they’d be very happy together for the rest of their lives. Their greatest adventure had only just begun.

What about you fellow fiction writers? How do you draw inspiration for creating your characters? Do you recognize traces of yourself in any of your stories?

by Naomi L. | June 12, 2013 | Blog, Creative Writing, Notable Authors |

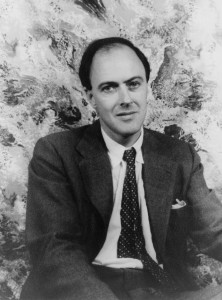

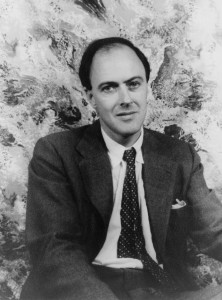

So last week, I talked about a book that I loved as a child: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Continuing on the subject of inspiration, I wanted to create another subtopic focusing on authors whose work has inspired me in my own writing, and it seems only fair to start with the same author of the wonderful book I’ve already reviewed. Kicking off the Notable Authors segment of my blog is storyteller extraordinaire and one of my favorite writers of all time: Roald Dahl.

Roald Dahl in 1954

Bio

Name: Roald Dahl

Pen Name: Roald Dahl

Life: Sept. 13, 1916 – Nov. 23, 1990

Gender: male

Nationality: British (born in Wales), Norwegian descent

Occupation: novelist, short story writer, screenwriter, fighter pilot (WWII)

Genres: children’s literature, fantasy, mystery, nonfiction

Notable Works: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Fantastic Mr. Fox, James and the Giant Peach, Matilda

My Favorite Works: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda, The Umbrella Man and Other Stories

Inspiration

Roald Dahl was my favorite author growing up, and with good reason. Having captivated me at the age of nine with his 1964 novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, he quickly drew me into his fantastic world with more children’s books like Matilda, Fantastic Mr. Fox, The Witches and several others. His unique style of storytelling was very entertaining to read, for he always seemed to know exactly how to paint a mental picture from the perspective of a child, which is much more appealing (and less patronizing) than an adult trying to describe the events of a story in a way that children will understand. Reading each of Mr. Dahl’s novels as a kid, I felt as though I were being told a story by someone who understood exactly how I saw the world, and who knew exactly what I wanted to find in the pages of a book. It may seem odd, but whenever I was reading one of his stories, I didn’t see him as just an author; I saw him almost as a friend.

Matilda and Miss Trunchbull, Matilda

(Illustration by Quentin Blake)

Something I always loved about Dahl’s children’s books was the fact that his heroes were usually children. Charlie Bucket, Matilda Wormwood, the unnamed protagonist of The Witches (named Luke Eveshim in the 1990 film), among others, all live incredible adventures before even having reached adolescence. For the preteen me, it was wonderful to read about heroes who were my age; it made me feel like it could just as easily have been me taking a tour through a magical chocolate factory, or developing telekinetic powers, or executing brilliant plans to defeat witches or cruel headmistresses or nasty adults of any sort. That’s another interesting detail about the author’s stories: just as the heroes are often children, the villains are often adults. And honestly, could anything be more relatable to a young reader?

But Mr. Dahl’s brilliant storytelling skills were not limited to children’s fiction. He wrote a fair amount of excellent short stories for older audiences; one such compilation – The Umbrella Man and Other Stories – contains some of the most delightfully creative short pieces I’ve ever read in a book. His autobiography, Boy: Tales of Childhood, includes hilarious accounts of events that I could hardly believe were true stories (my personal favorite is the Great Mouse Plot of 1924, which romantic comedy fans may remember as the story Meg Ryan reads to the children in the bookstore in the 1998 film You’ve Got Mail), but which certainly explain the colorful stories he would go on to write later in his life. With numerous awards and tremendous merit to his name, it’s clear that Dahl was talented at entertaining readers of all ages alike.

Roald Dahl is one of my heroes. He introduced me to a magical world that I could visit anytime I wanted to escape from reality, and he was the first author ever to inspire me to pursue creative writing. His stories have touched me and will remain forever embedded in my heart, and for that, I will always admire him as one of the greatest storytellers whose work I’ve had the pleasure of reading. Thank you, Mr. Dahl, for your wonderful gift! You will never be forgotten.

The main problem with the fairy tale characters is that they’re “plug-in” types. They’re like mass-produced instant ramen noodles: conveniently cheap and easy to prepare, but not exactly a healthy choice. When basic character profiles are used excessively over the years, they inevitably become clichéd and uninteresting. And intelligent readers don’t want clichéd and uninteresting; they want to see through the action on the pages to glimpse another level of the characters. They want depth.

The main problem with the fairy tale characters is that they’re “plug-in” types. They’re like mass-produced instant ramen noodles: conveniently cheap and easy to prepare, but not exactly a healthy choice. When basic character profiles are used excessively over the years, they inevitably become clichéd and uninteresting. And intelligent readers don’t want clichéd and uninteresting; they want to see through the action on the pages to glimpse another level of the characters. They want depth.

Recent Comments